The four Doctors Strangelove

Who was the real-life Dr Strangelove? Four names have been acknowledged as inspirations. Here we'll see who they were and why were they chosen.

Picture, if you will, three Jews and a Nazi serving as the real-life inspirations for a deranged scientist building weapons of mass destruction for the United States (who is a Nazi, by the way).

As many people know, this actually happened. In Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece Dr Strangelove, the titular character was created after four brilliant men — three scientists and one engineer:

John von Neumann and Edward Teller, who worked in the Manhattan Project and garnered a reputation of fanatic Cold Warriors (Teller went on to become known as “the father of the Hydrogen Bomb”);

Herman Kahn, a scholar at RAND Corporation, who famously claimed that a nuclear war between the United States and the Soviet Union could be “winnable” ;

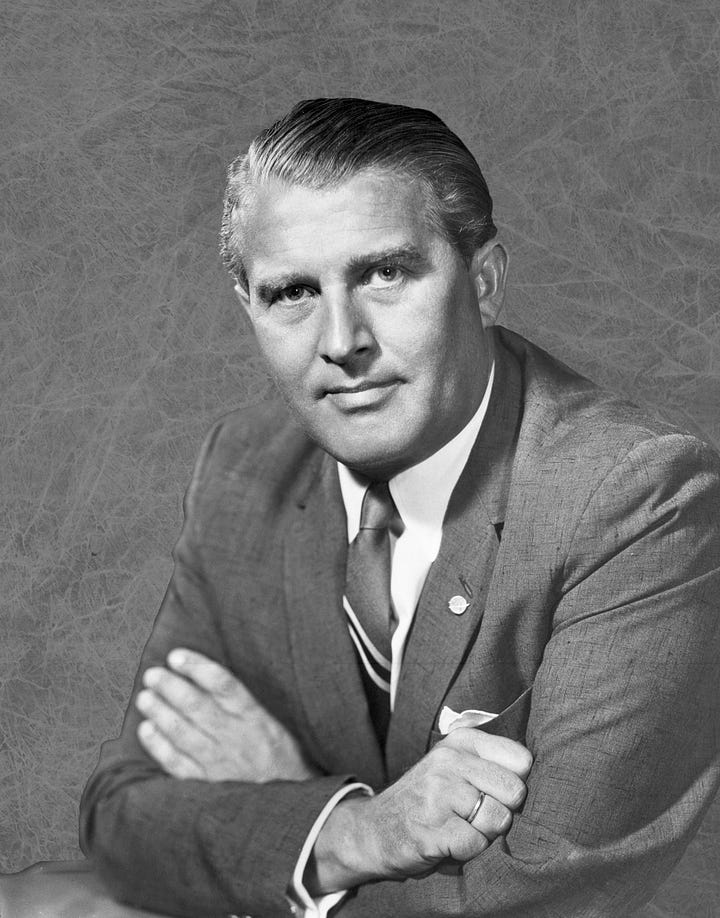

and the SS Officer Wernher von Braun, the engineer who invented the supersonic V-2 rockets that terrorized London, Antwerp and Liège at the end of World War 2, and later led the Space Program that sent Americans to the Moon.

A nightmare to laugh at

Doctor Strangelove doesn’t appear in the novel the film was based on (the thriller Red Alert). It was an original character, created by Kubrick and screenwriter Terry Southern. Kubrick spent a long time thoroughly researching information about nuclear weapons, the risk of nuclear war, and the politics of the Cold War. His initial idea was adapting the book into a serious film, but as he was studying the subject, all the absurdity of the “logic” behind the devised strategies became impossible to ignore. Doctor Strangelove was created out of this realization.

Kubrick explained in an interview why he changed his mind:

“The only way to tell the story was as a black comedy or, better, a nightmare comedy, where the things you laugh at most are really the heart of the paradoxical postures that make a nuclear war possible.”

The film is indeed a dark, nightmarish comedy, starting with American general Jack D. Ripper (the name couldn’t be more on-the-nose) about to order a bomber squadron to attack the Soviet Union. His justification is as outlandish as it can be, but it was just an exaggerated version of the “Red Scare” that had engulfed America since the 50s.

“I can no longer sit back and allow Communist infiltration, Communist indoctrination, communist subversion, and the international Communist conspiracy to sap and impurify all of our precious bodily fluids.”

When the film was released, the idea of officers deciding to launch attacks on their own was thought preposterous. Actually, before the film started, a disclaimer by the US Air Force assured the public that that wasn’t true — but it was.

Kubrick was right. Ridiculing the whole affair was the best way to highlight its insanity.

The doctor comes late

Doctor Strangelove intervenes only 51 minutes into the film, bound to a wheelchair, with a creepy smile, and his right arm always struggling to make the Nazi salute (as if it had a will of its own). It’s a magnificent performance by Peter Sellers, who played two other characters: British Captain Mandrake, and American President Merkin Muffley.

The doctor speaks with a thick accent about the doctrine of deterrence that became pretty much the consensus throughout the Cold War:

“Deterrence is the art of producing in the mind of the enemy... the fear to attack.”

Something along these lines would be conceptualized as Mutually Assured Destruction, or MAD, an appropriate acronym. In the last moments of the film, the Soviet Ambassador reveals that the USSR was about to automatically trigger what he called the “Doomsday Machine”, in response to an attack by a rogue American bomber (the only one remaining from the squadron).

Doom and gloom

True to its name, the “Doomsday Machine” would turn the Earth into a wasteland. Strangelove points out that, had this been publicly announced, both sides would know that a nuclear strike would mean mutual destruction. Hence, deterrence (this idea was originally floated by Herman Kahn, as we’ll see later).

Just like the idea of an officer deciding to launch a nuclear attack on his own, the “Doomsday Machine” was also dismissed as absurd.

Yet something of this sort was built. I’ll leave this to a future post.

The four real-life figures mentioned above dealt with these issues one way or another — but very seriously, and with potentially catastrophic consequences. Who were they?

From Hungary without love

John von Neumann and Edward Teller were born in Budapest in the beginning of the last century — a time of cultural and intellectual effervescence in the Austro-Hungarian Empire. They met each other as young adults, and a few years later they had moved to the United States, like so many other Jewish exiles. It was not a good idea to be in Europe (especially in Germany) in the 30s.

They would become great friends, working together in Project Manhattan, the ultra secret, huge enterprise to design and build an atomic bomb in time to be used in World War 2. It succeeded.

Unlike other scientists who took part in the project, von Neumann and Teller never regretted it or revealed second thoughts about its uses. Actually, after the USSR successfully tested its first atomic bomb, their stance towards nuclear weapons hardened. Their families had an unpleasant experience (to say the least) with Béla Kun’s brief but tumultuous Communist regime in Hungary in 1919, and their fervent anticommunism could be traced back to that period.

The prodigy

A polymath genius who excelled in whatever field he decided to explore, von Neumann made seminal contributions to disciplines such as Mathematics, Logic, Quantum Physics, and Computer Science (the standard computer design is still called a von Neumann architecture).

Von Neumann developed (with economist Oskar Morgenstern) Game Theory and its application to Economics. He also contributed to Artificial Intelligence and what much later would be called Artificial Life. After Project Manhattan, he contributed to the design of the H-Bomb. And to think that he was only 53 when cancer killed him. He spend his final months bound to a wheelchair — just like Doctor Strangelove.

His was a sharp and focused mind, and personally von Neumann was what could be called “the life of the party”: always well dressed, witty and jocular, he was the opposite of the egghead stereotype.

He could also be disconcertingly cynical. As when, hopefully in jest, he had this to say about a first strike against the Soviets:

“If you say why not bomb them tomorrow, I say why not today? If you say today at 5 o’clock, I say why not one o’clock?”

This was before MAD came to be a reality. The idea of an overwhelming first strike against the USSR to prevent it from amassing a nuclear arsenal — in case it didn’t accept a “world government” — was publicly defended by many people shortly after World War 2, including otherwise pacifist Bertrand Russell and Winston Churchill.

Strange highs and strange lows

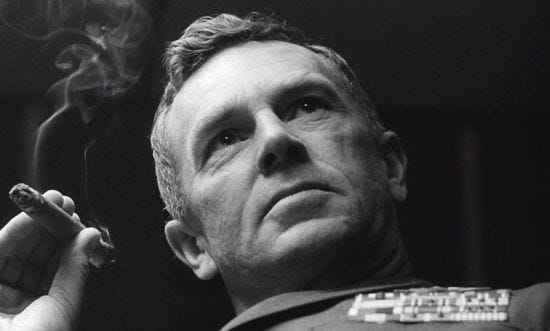

The contrast between the flamboyant von Neumann and his great friend, Edward Teller, couldn’t be starker. A tortured personality, Teller was as capable of great scientific and engineering feats as of despicable acts of character assassination. He could be kind and generous in private and mean in public.

Teller was actually called the “the real Doctor Strangelove”, and hated it. He hated a lot of things, in fact — especially the Soviet Union and its agents, who he saw everywhere. As an early advocate of “peace through strength”, he was a staunch defender of building more powerful weapons before the communists did it (in other words, an arms race). So much so that many years later, in the 80s, he persuaded President Ronald Reagan that the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI, known as “Star Wars”) was feasible.

Teller spent some ten years researching designs for the hydrogen bomb, until the first one was detonated in 1954 (the tests were humanitarian and environmental disasters that unintentionally gave rise to Godzilla). This granted him the title of “Father of the Hydrogen Bomb”. He wasn’t, though (or at least he wasn’t the only one). Teller developed and improved the first successful model, designed by mathematician Stanislaw Ulam — but he never gave Ulam the credit he deserved.

Bad hombre

If you think this is bad, just look at what Teller did to J. R. Oppenheimer, head of the Los Alamos Laboratory during the Manhattan Project, and whose name is the first people associate with the bomb. Oppenheimer was accused of being a communist spy in the mid-50s (remember, it was the American 50s). Most of his colleagues testified in his favour, but Teller made a point of volunteering to testify against him (he held a grudge against Oppenheimer since the times of the Manhattan Project). It was not an outright accusation, but the innuendo was damaging enough. Oppenheimer fell into disgrace, and so did Teller — he was never forgiven by his fellow scientists.

Isidor Rabi, who won the Nobel of Physics for the discovery of nuclear magnetic resonance, called Teller "an enemy of humanity". Was he? Well, to the extent that whoever designs, builds, or advocates for nuclear weapons is an enemy of humanity, yes. But perhaps his worst enemy was himself.

Shock and awe

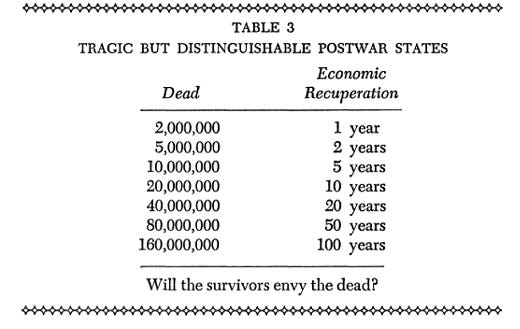

This is a table from Herman Kahn’s book On Thermonuclear War:

If simply the act of considering these estimates looks outrageous, well, that was exactly the point. Herman Kahn liked to shock — and wasn’t afraid to talk and write about scenarios deemed unthinkable, or even outright immoral (Thinking About the Unthinkable was the title of another of his influential books). He also revelled in being the centre of attention in public occasions. And not only because he was literally a very big man.

An interdisciplinary maverick, Kahn navigated seamlessly between Physics, Mathematics, Statistics, Systems Analysis, and Game Theory, often in search of novel insights. In the 50s he became a star of RAND Corporation (a think tank originally linked to the military, later turning into a non-profit agency for research in public policy and geopolitics). His main interest was devising scenarios for nuclear war, how to win it, and what would be the possible consequences.

Lucky strike

For Kahn, deterrence meant first and foremost a credible “second-strike capability”, or in other words, making sure to the opponent that retaliation would be devastating. And to be credible, Americans should at least be seen as willing to die by the millions if that meant defeating the Soviets and ensuring a (sort of) normal life for survivors afterward.

Kahn studied many variants of conflict, involving millions of lives lost, as well as defending the construction of a large number of fallout shelters. He believed that it might be possible to “win” a nuclear war.

“Despite a widespread belief to the contrary, objective studies indicate that even though the amount of human tragedy would be greatly increased in the postwar world, the increase would not preclude normal and happy lives for the majority of survivors and their descendants.”

And last but not least, in On Thermonuclear War Kahn also speculated about a “Doomsday Machine”, meant to never be used except as a deterrent. This went straight to Dr Strangelove: one of the doctor’s first lines is about a Doomsday Machine project studied by the “BLAND Corporation” — a clear and mocking reference to RAND.

The Soviet device in the film was obviously also inspired by Kahn’s speculations, as was the doctor’s remark that it could only work as a deterrent if its invention was made public (if not, “this idea was not a practical deterrent”).

In fact, Kahn was one of the scientists that Kubrick met to discuss nuclear war, and we can see how much the director got from their conversations — the war as “winnable”, a cold calculus of an “acceptable” number of casualties (by General Turgidson, played by George C. Scott), and a massive number of shelters for survivors. Kahn even believed he had the right to royalties (Kubrick made clear that he didn’t).

Iron sky

The first long-range ballistic missile hit London on September 8, 1944. It was a V-2 rocket, one of the Wunderwaffen (wonder weapons) with which Nazi Germany hoped to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat. They didn’t.

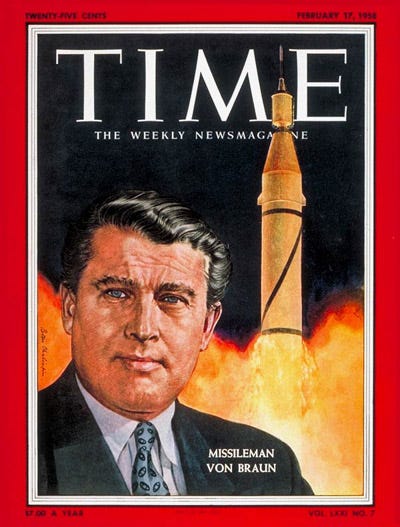

What they did was, unwittingly, to start the Space Age. The revolutionary V-2 was the first rocket to leave the atmosphere (during part of its trajectory). His inventor, the brilliant engineer Wernher von Braun, was brought to the United States after the war to lead the enormous technological and economic effort to put a man on the Moon. And he did.

Von Braun was an SS Officer, but it’s generally accepted that this was the only way he could progress in his career living in Germany (and he didn’t want to leave; born into nobility, von Braun was a nationalist). Rockets and space exploration were his passion since childhood, and his talent as an engineer led him to become the director of the famous Peenemünde Rocket Centre. The V-2 missiles were a triumph of his innovative mind. He argued that building them was a national duty, since his country was at war.

The revengers

The “V” in V-2 stood for Vergeltungswaffe: “Revenge weapon”. The Nazis were not at all subtle, but at least they made their motivation clear. By the end of the war, their missiles had killed around 9,000 people in the attacks. But they were not the only casualties: the weapons were built in large underground facilities by thousands of slave labourers — and more than 20,000 died of starvation, exhaustion, maltreatment, torture, executions, and whatnot.

And herein lies the main case against von Braun: was he involved in the forced labour regime?

From zero to hero

He always denied it, even though, as the project leader, he certainly went underground to check how things were going. He admitted having seen the awful working conditions, but that was all. After his death in 1977, however, accusations of direct involvement were made, portraying him as a cynical man only interested in a successful career.

When Dr Strangelove was released, von Braun was already a household name in the United States (he surrendered to the Americans in 1945, and was brought to the US together with many other Nazi scientists). He figured on the cover of Time magazine, appeared on television and, after the successful Moon landing, became a hero.

Von Braun’s image was carefully managed by successive US governments, which tried to cover up his past. The campaign was largely successful, but there were always people in the know — and this leads us to the climactic scene in the film.

See you at the bitter end

We lived on the brink of disaster for more than 40 years, and were lucky enough to avoid it. But Dr Strangelove, like other films, remains as relevant as ever — or even more so these days, since our political and military leadership is in the process of going full demented. Looks like satire is real life now.

But satire can only go so far, and this is an important lesson from the film. The unforgettable ending, with Vera Lynn singing We’ll Meet Again — one of the most popular songs during World War 2 —, is not nightmarish comedy anymore. It’s just a nightmare.

Does anybody here remember Vera Lynn?