If you bomb it, he will come

The first Godzilla is not a gaudy monster fest. It's a dark, sombre, and highly political film.

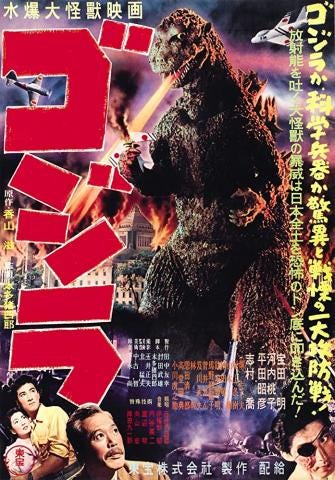

Everybody knows Godzilla. The lizard-like beast, stomping miniature Tokyo or other cities, and fighting other bizarre creatures with his signature atomic breath, became the paradigm of the giant monster movies (known as the kaiju genre). Men inside awkward suits played the monster and his enemies, and old-fashioned special effects added to the fun — replaced in recent years by digital imagery, which detracts from the campy spectacle.

But it was not always like that.

Dealing with traumas

The first Godzilla film, or Gojira in Japanese, was a serious affair. Released in 1954, it was a bleak, depressing reflection on nuclear weapons, the use of science for destructive purposes, and unleashing powers that we cannot control, with nature taking revenge. Filmed in black and white, and with a beautiful and ominous soundtrack by Akira Ifukube, the film deals fair and square with the trauma of the atomic attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki just nine years before, and their aftermath.

Producer Tomoyuki Tanaka was straightforward about their motivation:

“The theme of the film, from the beginning, was the terror of the bomb. Mankind had created the bomb, and now nature was going to take revenge on mankind”

But the atomic bombs were not the only references to the war. The film also doesn’t forget the firebombing of Tokyo, that killed as many as 100,000 people. The fires in the capital during Godzilla’s attack are eerily similar to the real images.

The (Tragically) Unlucky Dragon

One of the first thermonuclear bombs (or hydrogen bombs), was tested by the United States in the Bikini atoll on March 1954. The “Bravo” Test was a mess: scientists underestimated the destructive power of the device by a factor of 3. The explosion had a yield of 15 megatons — the energy equivalent to 15 million tons of TNT —, or more than a thousand times the energy released by the bomb in Hiroshima.

Not far from the test was the hapless Japanese fishing vessel Daigo Fukuryu Maru, or Lucky Dragon Nº 5. The crew was exposed to radioactive fallout, and all 23 fishermen suffered radiation sickness, resulting in the death of the radio operator. The American government refused to acknowledge that he was killed by the “ashes of death” (as a Japanese newspaper called it).

Straight to the point

Gojira starts in an uncompromisingly direct way, with a fishing vessel (a reference to the accident a few months earlier) mysteriously bursting in flames after a blinding light hits it — caused by some strange phenomenon coming from the ocean. The ship submerges with all the sailors sinking to their deaths.

Other ships are sent in rescue missions and all face the same fate. Afterwards, a storm strikes Odo Island, and palaeontologist Kyohei Yamane (played by Takashi Shimura, of Rashomon and The Seven Samurai fame) detects large footprints — which turn out to be highly radioactive: the Geiger counter goes through the roof. After studying them, he concludes that a creature from the Jurassic period was awoken by nuclear tests. He announces it to the Japanese government, and in this and other subsequent official meetings, lively debates ensue, involving nuclear weapons and Japan’s diplomatic relations (with a country that is not named, but it’s plainly obvious which one it is).

Not an evil genius

Throughout the film there are references to nuclear weapons and even to the Nagasaki bombing. While Godzilla’s threat looms, we are introduced to Professor Yamane’s daughter, Emiko (Momoko Kochi), her boyfriend Hideto Ogata (Akira Takarada), and her ex-fiancé-to-be Daisuke Serizawa (Akihiko Hirata). Serizawa is the typical scientific genius who unwittingly creates a weapon of mass destruction (the “Oxygen Destroyer”). He served in the war and lost an eye, though the psychological damage might be even worse.

Serizawa refuses to make his invention public because it will inevitably be used for nefarious ends (a clear parallel with nuclear weapons). But in the end, with Godzilla rampant, he will have to make the ultimate choice (no spoilers here).

Scar tissue

Director and writer Ishiro Honda served in the Imperial Army during WW2 in China for nine years (there’s no evidence that he took part in the unspeakable atrocities perpetrated by the Japanese Army). A long time friend and collaborator with Akira Kurosawa, Honda was able to accomplish the feat of making a humanist manifesto out of a kaiju movie.

Honda was forced, like other soldiers, to visit Hiroshima in his return to Japan, and the experience haunted him for the rest of his life. It was also the inspiration for the film. Godzilla wouldn’t be just another monster (like King Kong, which was an obvious influence). He would be the embodiment of the nuclear nightmare:

“If Godzilla had been a dinosaur or some other animal, he would have been killed by just one cannonball. But if he were equal to an atomic bomb, we wouldn’t know what to do. So, I took the characteristics of an atomic bomb and applied them to Godzilla”

And it was a real, physical embodiment. The special effects director, Eiji Tsuburaya, decided to use miniature buildings to represent Tokyo, and put an actor inside a monster suit — using stop-motion animation would take too long. Godzilla’s skin was made to resemble the keloid scars of bomb survivors.

The sorrow and the pity

Godzilla appears in full only 45 minutes into the film, when he emerges from Tokyo Bay. Attacked (fruitlessly) by the military, he angrily starts his rampage through the capital. It’s almost 25 minutes of utter destruction, and his “atomic breath” wipes out men, women, and children in scenes that are horrific and pitiful. Credit here to the brilliance of Honda’s directing, transforming into a terrifying experience what could easily slide into ridicule (a man inside a monster suit destroying miniature models of buildings and infrastructures).

A woman tells her daughter, moments before they’re pulverized, that they will finally meet the girl’s deceased father. After the catastrophe, many scenes remind us of the realities of a nuclear attack: hospitals are overwhelmed with wounded and dying people, some of them with severe burns. A kid is examined with a Geiger counter that shows he is seriously irradiated. These and other desperate situations left many Japanese audience members in tears.

American whitewashing

Two years later, the film was released in the United States and, not surprisingly given the issues at stake, in a sanitized version. Footage of actor Raymond Burr, as a journalist in Japan, was hammered into the original film, and almost all references to nuclear weapons were eliminated.

The result was a cult monster movie (check the poster below) and Godzilla: King of the Monsters became the reference for Western audiences — until the original was finally released in the early 2000s, forcing a complete re-evaluation.

Still a taboo

William Tsutsui, an American scholar who studies the fictional monster as a cultural phenomenon, and is known by students as “Professor Godzilla”, believes that this is symptomatic of an attitude among the American public — even after all these years:

“It still is the case that they cannot get their minds around the nuclear issue and American culpability in the atomic bombings in Hiroshima and Nagasaki”

But if it weren’t for the campy classics mass-produced in Japan (and later the US) from the 50s onwards, perhaps we wouldn’t be able to watch the film that gave rise to it all — albeit in a completely different direction. A true eye opener.

An interview with William Tsutsui, “Professor Godzilla”

An article on the historical context of the film

The three eras of Godzilla