WarGames: life imitating cinema imitating life

The classic film with Matthew Broderick and Ally Sheedy was much more than science fiction.

WarGames was a great film about the madness of nuclear brinkmanship, the risk of Armageddon by accident, and the dangers of Artificial Intelligence. And it also inspired a whole generation of hackers, at a time when computer and network security was practically nonexistent. Actually it was thanks to the exploits of fans of the film that “hacker” started to become a household word.

In the film, a teenager called David Lightman (Matthew Broderick) uses his computing skills to penetrate many systems — his school (to change his grades), Pan Am (for flight reservations) and his main interest, computer games. His friend Jennifer Mack (Ally Sheedy), who doesn’t know a thing about computers (as most people then) becomes fascinated and goes along for the ride.

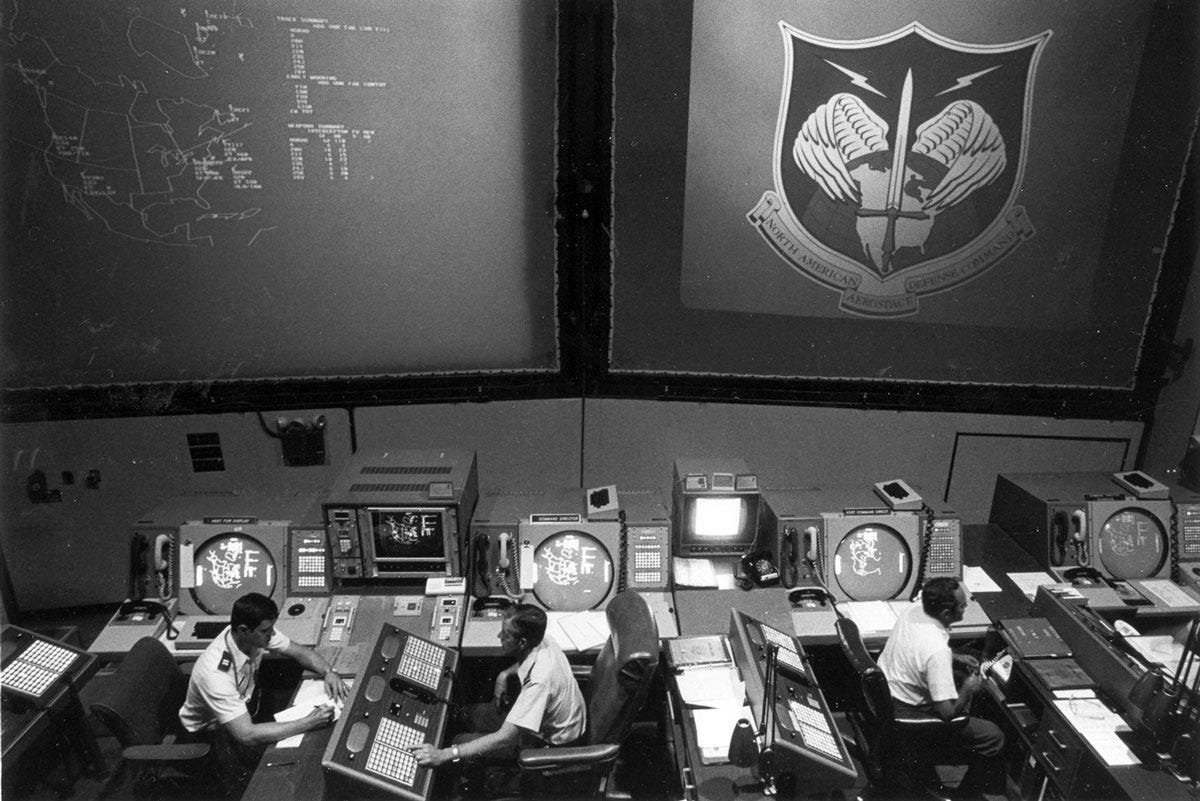

But one day, while believing he had accessed a brand new computer game, he actually entered the computer system of NORAD — the North American Aerospace Defense Command, that tracked 24/7 all the movements of Soviet troops, submarines, bombers, satellites, and alerts of nuclear missile launches. Worse: NORAD just put in place the supercomputer WOPR, with an Artificial Intelligence that spends all the time playing nuclear war games in all kinds of scenarios.

When David and Joshua (The AI’s name) start playing “Global Thermonuclear War” and David chooses to be the Soviets, NORAD’s warning displays show an overwhelming missile attack against the United States. All pieces are now in place for a wild ride until the final credits.

When the simulation was real

What many people don’t know is that the basic plot of the film was inspired by real events, one of which was eerily similar: on November 9, 1979, NORAD detected 1,400 incoming Soviet missiles. For six minutes the fate of the world hung in balance, until it was found out that the “attack” was actually a simulation — from a tape loaded by mistake into a computer.

The tape was meant to be used for training, but almost spelled doom. Apparently the NORAD system was too complex and could lead technicians to error. Not very reassuring (a previous telling of this story included a dramatic phone call to Zbigniew Brzezinski, National Security Advisor to President Jimmy Carter, but recently declassified documents cast doubt on the account).

Reagan’s question

In the morning of Wednesday, June 8, 1983, during a meeting in the White House, President Ronald Reagan turned to General John Vessey, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and asked a question that nagged him since he had watched WarGames the previous weekend: “Could something like this really happen? Could someone break into our most sensitive computers?”

Vessey came back with the answer the following week: “Mr. President, the problem is much worse than you think”.

Worse indeed. In the early 80s, computer systems were being adopted at a fast pace by many government agencies, financial institutions, businesses big and small, schools, hospitals and what have you. And with enough skill and patience, someone could enter and explore the innards of basically any institution. After Reagan watched the film, the first pieces of legislation against “cybercrime” were enacted.

Hackers in the spotlight

If Reagan saw in WarGames a threat, a group of teenagers from Milwaukee saw an opportunity. In the true hacker tradition, they were fascinated by computers and the possibility of connecting to systems they were not supposed to explore. Their goal was not to commit crimes, but to enjoy the exploration. And like many other young people, they loved WarGames. Hacking was cool after all.

They called themselves the “414s”, adopting their city’s area code, and started hacking in earnest. The group soon was able to enter the Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center and the Security Pacific National Bank, among other systems. It was really easy, since in some cases the username was “system” and the password was also “system”. Unbelievable, isn’t it?

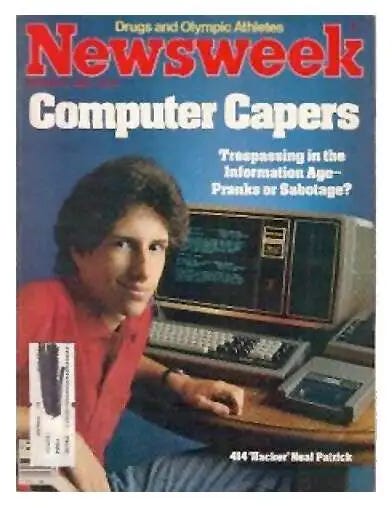

But some anomalies in Sloan-Kettering records called the attention of the FBI, which started investigating. When the 414s dared infiltrate the Los Alamos National Laboratory (where the American nuclear program took off during World War II), it was game over. With the exception of Neal Patrick, who was still a minor, the group risked facing jail time — but, since there was no law against hacking yet, they ended up convicted of “phone harassment”. Two years’ probation and a $500 dollar fine were all they got.

Meanwhile, Neal Patrick became a sort of media star, appearing on television, newspapers and magazines, and even testifying before Congress about computer security. The Newsweek cover of September 5, 1983, used the word “hacker” for the first time in mainstream media. David Lightman would be proud.

The story of the 414s was told in the short documentary The 414s: The Original Teenage Hackers (you can watch it here).