Akira: the manga, the anime, the bomb: Part 1

Katsuhiro Otomo's hugely influential masterpiece made manga and anime popular worldwide. It's a cyberpunk dystopia, in the shadow of the ultimate weapon.

Picture, if you will, a new Tokyo built after the old city was destroyed in World War 3. Young biker gangs ruthlessly roam “NeoTokyo” fighting each other while rebel groups engage in violent confrontations with the police and the military. The government secretly keeps three children with psychic powers — children whose faces look like they’re 80 years old. And an overwhelmingly destructive entity is set to resurge and turn everything into ruins. Again.

This is the world of Akira, a masterpiece created by the genius of Katsuhiro Otomo, who managed to revolutionise both manga and anime (the Japanese style of graphic novels and animated films, respectively) with this cyberpunk saga.

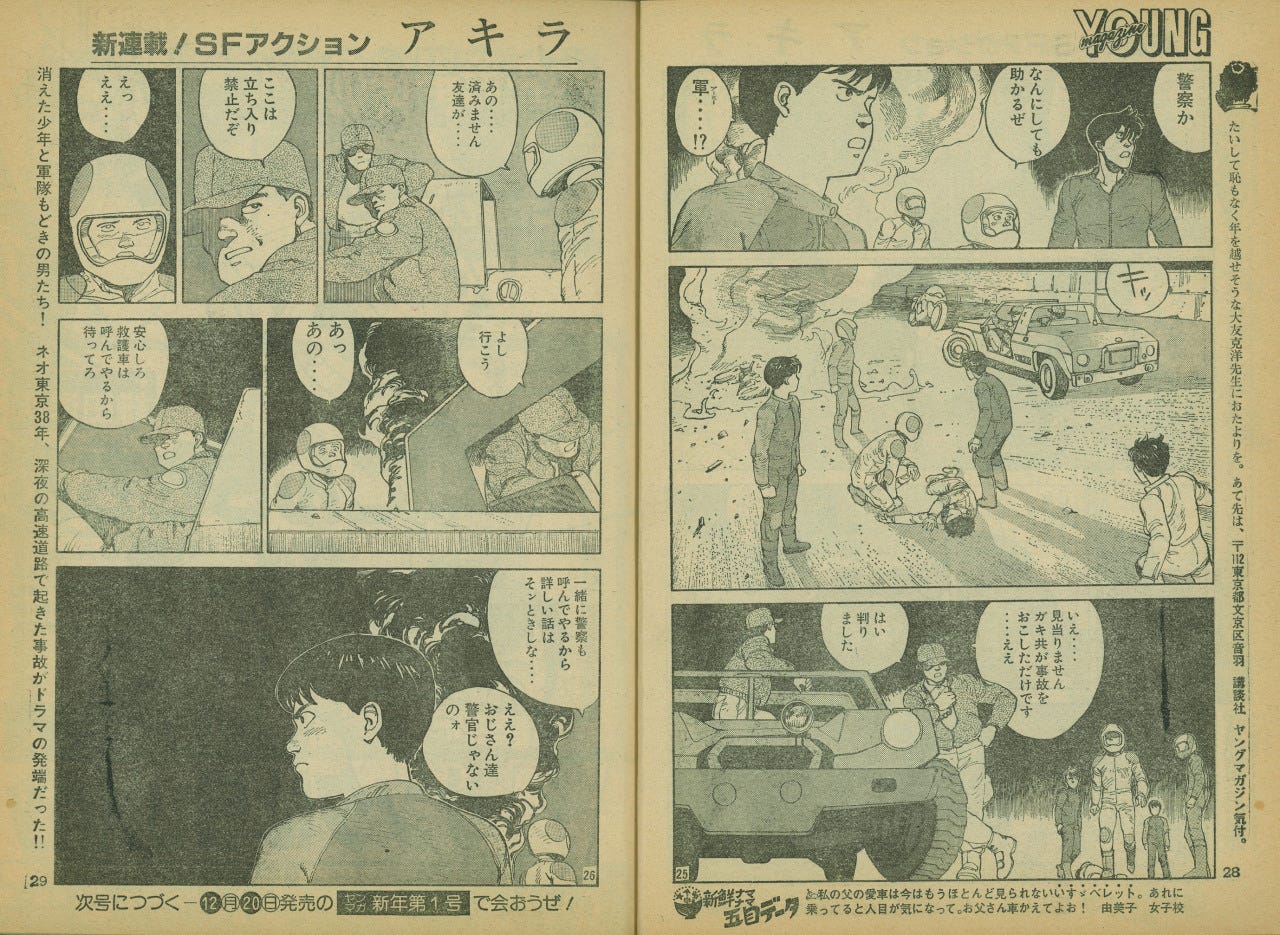

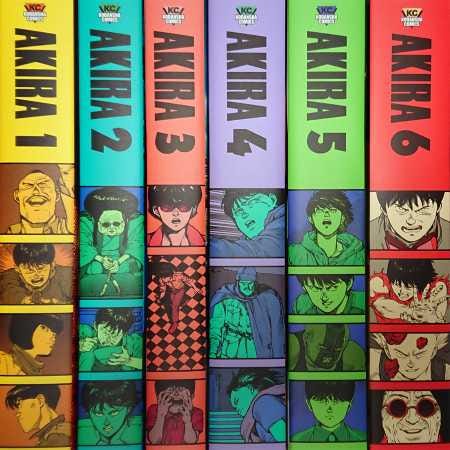

The manga was issued biweekly in Japan from 1982 to 1990 in Youth Magazine, published by Kodansha. The chapters were gathered in six volumes, with more than 2,000 pages in total, from 1984 to 1993. An English version of the graphic novel, published by Epic/Marvel in 38 instalments (from 1988 to 1995), garnered universal acclaim.

It’s not hard to see why. Akira is visually arresting, and Otomo has a gift for intricate detail. The manga is a compelling page-turner, with a complex story, well-developed character arcs (there are many), and unexpected twists — not the least about the titular character.

The manga is of such an epic scope that it will be the only focus of this article. Part 2 will be dedicated to the anime, and a comparison between the two.

Under neon loneliness, motorcycle emptiness

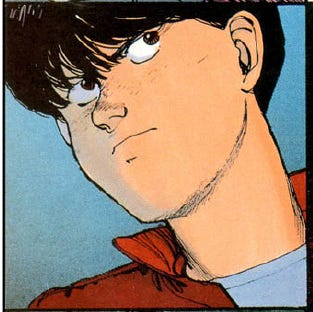

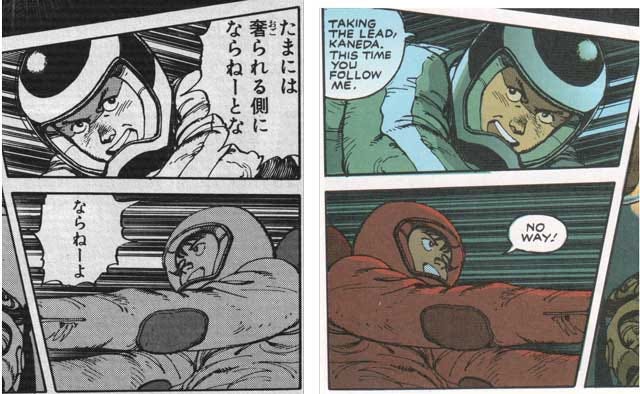

The year is 2019, one year before the Neo-Tokyo Olympic Games (coincidentally, the real-life Tokyo Olympics were also scheduled for 2020, but were delayed one year due to the Covid pandemics). We start by following a biker gang led by Kaneda, a brash teenager who drives an impressive machine.

Among the other gang members is Tetsuo, Kaneda’s childhood friend (a friendship forged in the orphanage). They battle other gangs, especially the Clowns, and from time to time dare ride to the old city, where a huge crater marks the spot where a devastating explosion happened 31 years earlier — the trigger for World War 3.

During one of those escapades, Tetsuo sees a weird child blocking his path. Unable to avoid the kid, the bike explodes just before hitting him. The little boy, chased by the gang, disappears out of thin air, much to Kaneda’s shock. The military appear just after the incident, seemingly looking for the boy, and leave quickly. Tetsuo is taken to a hospital.

The kids are not alright

The weird little kid, with the face of a very old man, is Takashi. He’s part of a secret government experiment with psychic children, with all sorts of powers (such as telekinesis, teleportation, and precognition), and identified by numbers. Like this one:

But not that pretty.

Three is the magic number

The children had been selected for a secret parapsychology project more than 30 years before, and only few survived the experiments. Three of them got stuck in childhood, but with disturbingly wizened faces: the little girl Kiyoko (Nº 25), and the boys Takashi (26) and Masaru (27). Kiyoko is so weak that she must stay in bed at all times.

The project went terribly wrong when Tokyo was destroyed. And this is why the three kids have been kept hidden all this time. They are administered drugs to tame their powers, which must be controlled to prevent the risk of a psychic blast — like the one that devastated the city 31 years before.

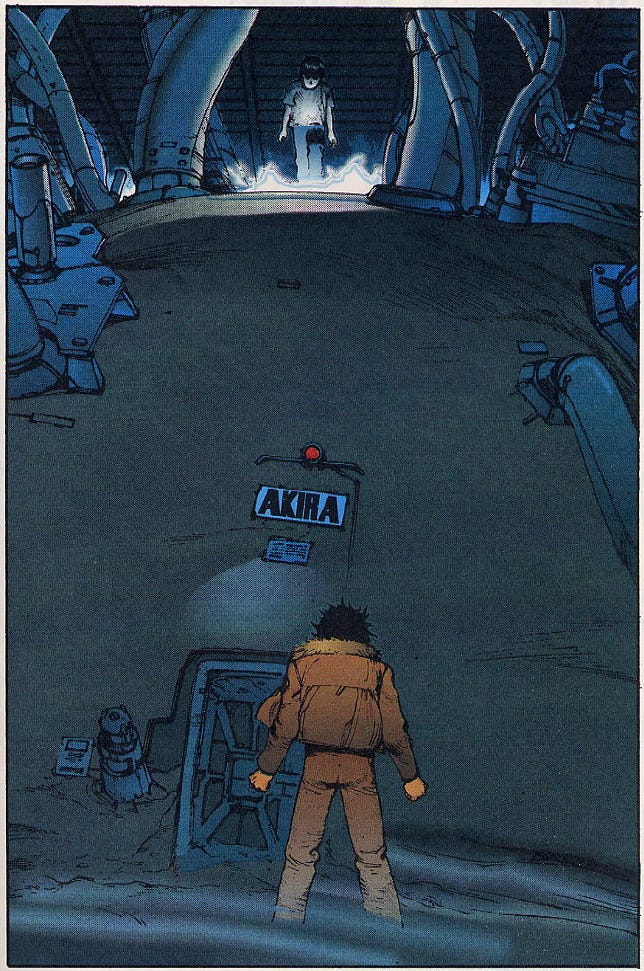

That blast had been delivered by Akira (Nº 28), by far the most powerful of them all. Unable to control his own power, he eventually flattened the city. The boy has been locked inside a cryogenic chamber ever since, under the site of the future Olympic stadium.

Colonel Shikishima, head of the secret project, is dedicated to avoid Akira’s resurgence. The boy must remain in cryogenic slumber, whatever the costs. But scientist Onishi, fascinated with psychic powers and full of scientific hubris, will mess everything up.

Resistance is not futile

Did I mention that the story is complex? There are other groups and interests involved, and they constantly interact with each other. An armed resistance against the authoritarian government has been raging for a long time, with constant and violent street battles. The resistance is secretly led by Nezu, an opposition politician.

From the resistance comes a key character: Kei, a smart, fearless, and resourceful girl. She and Kaneda don’t get along well when they meet, but later we will have one of those will-they won’t-they situations. I won’t tell.

Kei wouldn’t go much far without the invaluable help of Chiyoko, a big (in many senses), very strong woman, well versed in fighting techniques and weaponry. On top of all this, she protects Kei from danger (including attempted rape) and offers sensible advice. A fascinating character.

Another powerful woman is Lady Miyako, a psychic who was subjected to the government experiments (Nº 19) and became blind. She leads a cult with a large following among the poorest, hungry population. A wise woman, she is able to work with various factions, and grows in importance as the story advances.

Other characters play minor or occasionally important roles, but I won’t talk about them. Sorry.

Confusion in his eyes that says it all

All well and good (no, not really), but then we have the elephant (or rather, the mutant) in the room: Tetsuo.

As you may recall, he suffered a serious accident when his bike exploded. This triggered his hitherto unknown psychic abilities — which turned out to be huge. And for someone deeply disturbed and with an inferiority complex, the result could only be catastrophic.

Unable to control his powers, in a path of death and destruction, he is eventually assigned a number in the series of psychic experiments.

Hello darkness, my old friend

There are many comings and goings in Tetsuo’s journey, but what is really notable about him is that his powers are second only to Akira; and Tetsuo is obsessed with meeting him — which eventually happens, against the efforts of all the parties involved. Now, it’s just a matter of time for another catastrophic event.

All this when we didn’t reach even one third of the series. And the catastrophe happens around the middle. Which doesn’t mean that the second half is not full of twists and turns, tension, disasters and violence.

Empire of the damned

Tetsuo creates and calls the shots in the “Great Tokyo Empire”, nominally led by Akira, with fanatical followers dumbfounded by their so-called “miracles” (actually the effects of their psychic powers). Clashes with the other groups, especially Lady Miyako’s, are rampant.

Meanwhile, Kaneda and Kei deftly move between different factions, with Kaneda confronting Tetsuo at every opportunity — theirs is a strong and complicated relationship.

Just when you think things couldn’t get any worse, an American aircraft carrier approaches the region (because, of course). Tetsuo takes control of one of its nuclear missiles — with the predictable consequences.

Tetsuo’s powers have been taking their toll not only on his mind, but on his body as well. He ends up morphing into a grotesque giant, a mountain of flesh with a creepy baby face.

We’re not very far from the end, and I said enough already. There will be more surprises, to be sure. Read it, if you will.

“High tech and low life”

Akira is a gruesome, disturbing, and at the same time action-packed cyberpunk dystopia. Also true to the genre, social criticism is everywhere: corruption, authoritarianism, violence, militarism, propaganda, meaninglessness, as well as the deleterious effects of scientific hubris and excessive reliance on technology.

The manga made its debut in the early 80s, when the cyberpunk genre took science-fiction by storm. Other masterpieces like the film Blade Runner and William Gibson’s novel Neuromancer appeared at the time — a time when the Cold War was close to getting hot, “neoliberalism” was rearing its ugly head and computers and networks slowly started getting everywhere.

Cyberpunk, though, doesn’t necessarily involve nuclear war — it’s about “high tech and low life”, as writer Bruce Sterling once pointed out. Akira, however (even if we discount the literal nuclear explosion caused by Tetsuo), looks saturated with images that call to mind what happened to Japan at the end of World War 2.

Otomo denies that nuclear war was an explicit motivation:

“I wanted to draw this story set in a Japan similar to how it was after the end of World War II — rebelling governmental factions; a rebuilding world; foreign political influence; an uncertain future; a bored and reckless younger generation racing each other on bikes. Akira is the story of my own teenage years, rewritten to take place in the future … I have no intention of expressing my political views or philosophical opinions.”

In another interview, Otomo says his inspiration was Tetsujin 28-gō, an anime TV series he watched as a kid.

“The grand plot for Akira is about an ultimate weapon developed during wartime and found during a more peaceful era. So the accidents and story develop around that ultimate weapon. If you know Tetsujin 28-gō, then this is the same overall plot.”

Tetsujin 28-gō was a giant robot the Japanese Army was building during World War 2, but its construction wasn’t finished when Japan surrendered. Afterwards, the scientist who created the robot gave it to his son. Otomo was such a fan of the show that he chose “28” as Akira’s number. The scientist was called Shotaro Kaneda, the name of the biker gang’s leader in Akira.

Mind blown

The references to World War 2 and an “ultimate weapon” in Tetsujin 28-gō are clear allusions to the traumatic events that haunted the Japanese for many years after the war. But as Otomo explained, even though that anime inspired him, he was not interested in making a political statement.

This doesn’t mean that the story and the settings can’t be highly evocative. For instance, this is one of the devastating psychic blasts:

And this is a famous picture of the first milliseconds of the Trinity Test, the first nuclear explosion in history:

Tetsuo’s monstrous mutation may be seen as a hyperbolic depiction of the deformities endured by people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki (and their descendants). And it’s hard not to remember another traumatic experience: in the story, the Americans carpet bomb what remained of neo-Tokyo. A reminder of what they did to the Japanese capital in the final months of World War 2.

Go West

Akira was one of the first manga to be entirely translated into English and adapted for the American (and Western) market. It took an insane amount of work. Manga are mostly published in black and white, serialized inside magazines — in the case of Akira, it was Young Magazine, which ran biweekly the 120 episodes of about 20 pages each.

The adaptation wasn’t made directly from the magazines. The collection of six volumes was used instead. This made things somewhat easier, but not that much.

Japanese is read from right to left, and from top to bottom. This means that a lot of changes had to be made: the balloons’ format had to accommodate not only Western writing (from let to right, read horizontally), but also the lettering to which readers are used. Kodansha translated the full text, but as everybody knows (or should), a purely literal translation doesn’t work at all in works of fiction. So it was necessary to adapt it. Remember: it was more than 2,000 pages.

For the same reason, the pages should be flipped (or mirrored), which can cause problems, like left-handedness becoming right-handedness. And since the anime, unlike the manga, is obviously not “flipped”, some odd inconsistencies are inevitable.

Finally, we have colouring. Another complex process, managed by Steve Oliff, who introduced computer colouring to achieve nuance and modulation. Akira was the first graphic novel to be digitally coloured. Oliff worked with Otomo throughout the whole process. Actually, Otomo was present in all aspects of the adaptation to the English version.

Tribute to a master

The two last issues (37 and 38) of Akira’s English version present, in the final pages, tributes by many big names in comics and graphic arts — like Moebius, Dave Gibbons, John Romita, and George Pratt. They created beautiful reinterpretations, including short stories about minor (and not so minor) characters.

Akira was such a success that the anime adaptation was produced and released in Japan in 1988, while the manga was still running (hence unfinished). This means that the two works, despite sharing the same overall theme, can be drastically different (and not just because of the inevitable simplification from the literary to the cinematic). We’ll see this in Part 2.

Check this out:

Understanding the serialization of Akira

Manga translation: Akira in the West

Akira in Colour: Steve Oliff

The first Godzilla is a dark, highly political film about the nuclear attacks on Japan

In Watchmen, superheroes run amok in a dystopia on the brink of nuclear war