Who watches the Watchmen?

The greatest graphic novel of all time is a reflection on power, ethics, and politics, on the brink of nuclear war

Picture, if you will, a world where American superheroes are real, and have been in action for decades. With their help, the United States won the Vietnam War. It’s 1985, and President Richard Nixon has just started his fifth consecutive term. The nuclear escalation between the US and the Soviet Union reached such a point that the end of the world is about to happen in a few weeks.

Welcome to the world of Watchmen.

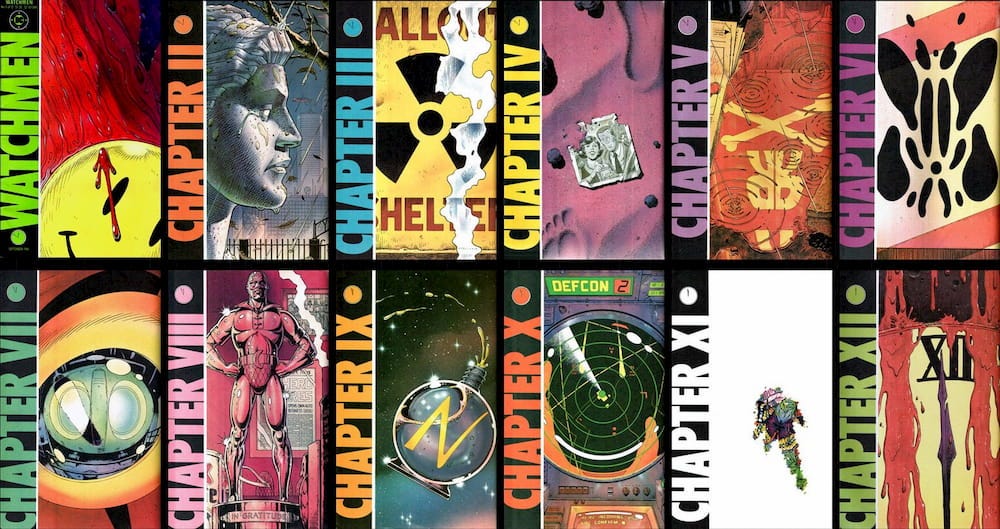

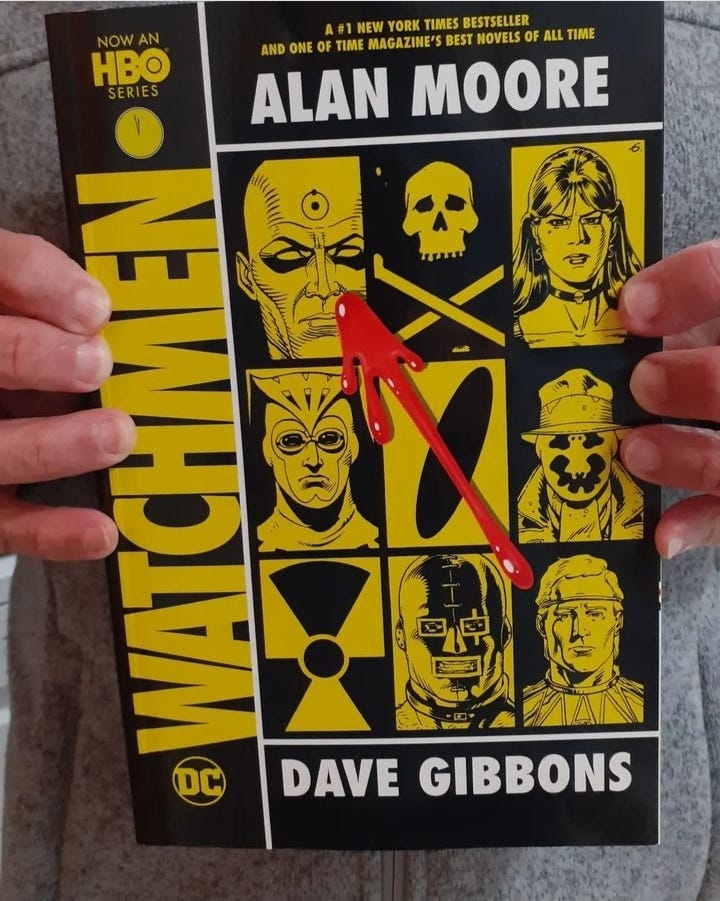

Released as a 12-part series between 1986 and 1987, Watchmen immediately caused an impact that still reverberates today. It is widely considered the greatest comic book story of all time, changing the genre forever — and, together with Frank Miller’s Batman: The Dark Knight Returns (1986), defining what would be known as “graphic novels”.

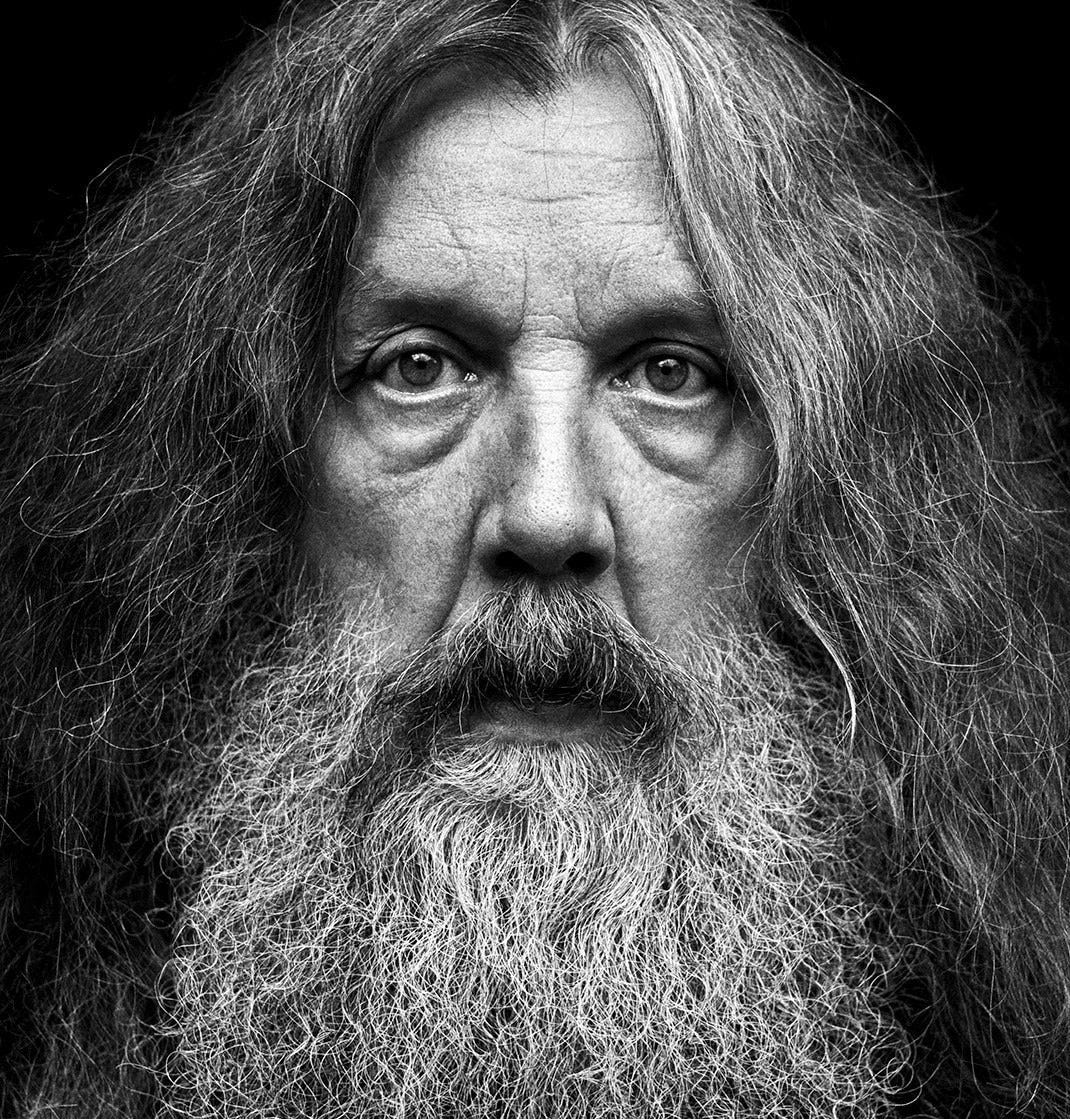

Written by Alan Moore (the genius behind V for Vendetta, The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen, Batman: The Killing Joke, and other classics), and illustrated by Dave Gibbons, the series was praised for its “deconstruction” of the superhero myth. The costumed vigilantes are all too human (with one exception), deeply flawed and at the same time sincerely willing to make amends to a decaying world — but in ways that are actually deeply harmful. Good intentions pave the way to hell.

Smile. You’re dead.

The very first cover (as well as the first page) shows how Moore managed to subvert the genre. The bloodstained smiley became a symbol of the series, reappearing in many unexpected ways. In an interview in 1988, Moore explained why that particular image was chosen, based on psychological experiments with children (I edited the quote because otherwise it would spoil the ending).

“The smiley face is evidently the purest symbol of innocence the human race has been able to come up with thus far. In that sense, putting a bloodstain across the eye of the face allows for a number of interpretations.

There’s the idea of smiling through the blood, the idea of a bloody joke … Also, since the badge is a symbol of innocence, and since superheroes have also represented a certain naïveté and innocence, you have a sense of lost or bloodied innocence, the end of this idea of truth, justice, and the American way. The very naïve notion of superhero goodness gets bloodied and knocked about.”

The dreaded clock

Another recurrent symbol is a representation of the Doomsday Clock, closing each chapter. It starts at 12 to midnight in Chapter I, and ends at midnight in Chapter XII. As each minute passes, blood slowly drips towards the clock. It fits the story, taking place during the most serious crisis between the two nuclear superpowers, and also strongly suggests fatefulness.

The smiley face itself can also be interpreted as a stylized representation of a clock: the bloodstain is like a minute hand pointing to twelve minutes to midnight.

This play with crossed visual references, allusions, and indications, contributes to a rich reading experience. The masterful work of Gibbons and colourist John Higgins explores the possibilities of the comics medium to the hilt. To this, Moore adds a complex narrative, going back and forth in time to tell the story of how costumed adventurers became a thing in America and how they affected (and were affected by) the country’s (and the world’s) history.

Who are these people?

There are six heroes (so to speak) in Watchmen. One of them (The Comedian) is murdered in the first scenes, and this crime sets the story going. Flashbacks tell us how costumed vigilantes came about, their relationships with their predecessors and with each other, the roles they played, their qualities and flaws.

At the end of every episode (except the last one) we have book chapters, newspaper headlines, medical reports, interviews in lifestyle magazines, letters, what have you — including details such as typewritten typos. It’s top notch character and environment building by Moore. It rewards repeated readings.

More than Superman

In the world of Watchmen, the popularity of costumed crimefighters reached their peak in the 60s and early 70s, with Dr Manhattan becoming the ultimate Cold War deterrent and almost singlehandedly winning the Vietnam War. Wait, what? How could he do that? Was he some kind of Superman?

More than that. He was like a god. And he changed everything.

From nuked to naked

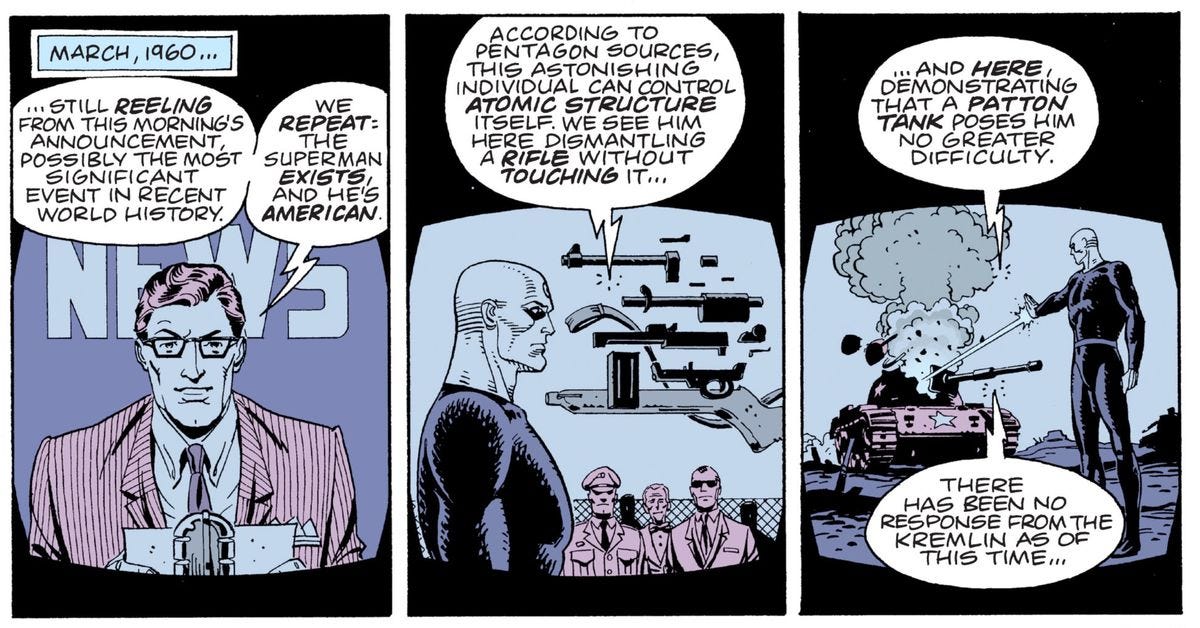

His name was Jonathan Osterman, a nuclear physicist, who suffered a freakish accident in a particle test chamber, turning into a tall, blue, naked man who could manipulate matter at the subatomic level, experience past, present, and future simultaneously, teleport, duplicate himself, change his size, and so on. He was also responsible for many technological advances that can be glimpsed throughout the pages.

Dr Manhattan was the only superhero proper, since his powers were well beyond the reach of humans. Almost immediately announced to the world by the US government, which gave him a name that was a very on-the-nose reference to the Manhattan Project, he was the best deterrent America could get.

Nixon now, Nixon now, more than ever, Nixon now

Even though he never felt totally comfortable with the role he had to play, Dr Manhattan promptly answered the call from the government to intervene in the Vietnam War. It didn’t take long for the Vietcong to start surrendering en masse, in a mix of terror and astonishment. Shock and awe, if you wish.

The United States won the war, and such was Nixon’s popularity that the Congress repealed the 22nd Amendment to the Constitution and abolished term limits. This is why he is still President in 1985.

Out of control

Nixon also counted on precious help from the Comedian, who had been working for many years as a violent and cynical government operative. After fighting in Vietnam with Dr Manhattan, he murdered the Washington Post’s reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein, ensuring that the Watergate burglary would never see the public light.

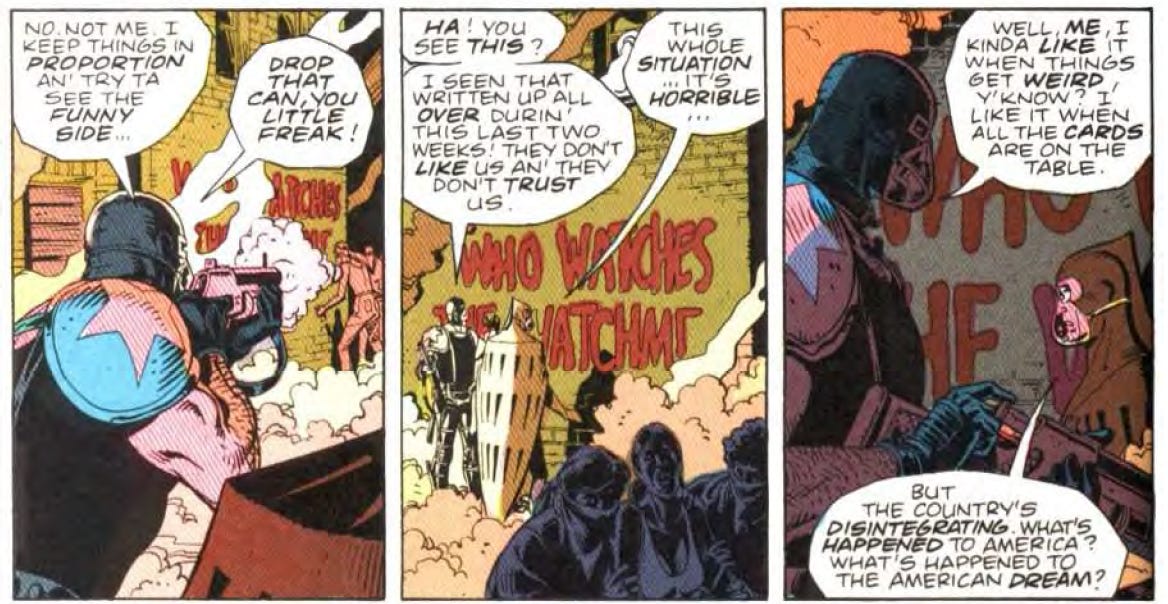

By the mid-70s, however, the heroes fell out of favour with the public, and things went sour after the Comedian (together with a reluctant Nite Owl) brutally suppressed a demonstration. The graffiti “Who watches the Watchmen” was a vivid expression of the sense that those masked vigilantes were out of control.

From crimefighters to criminals

This led the government to pass the Kleene Act, outlawing costumed crimefighters. At the beginning of the story, only two are still active: Dr Manhattan, who is such a big strategic asset that he keeps working for the government, and Rorschach, a one-man-army obstinate psychopath who uses all methods available to “clean” New York City of scum. Think Travis Bickle as an analogy. The main differences with the taxi driver are that Rorschach is not completely deranged and keeps a detailed diary that works as a kind of voice-over in many situations.

His mask, with a constantly moving ink-blot, is a kind of “live” Roschach psychological test, and there’s a terrifying moment when he uses the test itself to maximal effect. He’s an outlaw, obsessed with the end of the world and suspicious of a dark conspiracy that… well, I won’t spoil it.

The remaining three protagonists are retired in the beginning of the saga. Ozymandias became a billionaire businessman. Silk Spectre and the aforementioned Nite Owl inherited their monikers and action style, she from her mother, he from the original Nite Owl, of whom he was a big fan. She is dating Dr Manhattan, which leads to some weird stuff. But many surprising twists await the reader.

Counterfactual, ma non troppo

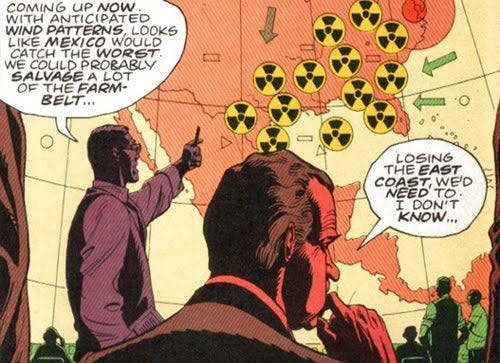

A key moment in the story happens when Dr Manhattan decides to stop being a deterrent (no more details here, of course). When this happens, the Cold War gets closer and closer to becoming Hot. And this shows how Watchmen’s counterfactual history is firmly grounded in the actual world.

The New York City we see in the graphic novel is as rotten, decadent, and dangerous as it was in the 70s and 80s (just watch a TV cop show or a film from that time). A belligerent President is in the White House, the Soviet Union is embroiled in Afghanistan, and nuclear anxiety is in the air.

Things deviate sharply from the real world again, and in dramatic fashion, when Nixon sets the state of nuclear alert to DEFCON 2, one step from actual hostilities.

Something big is about to happen, but I won’t tell you what it is.

The lesson not taken

Today we’re all used to gritty, dark, superhero comics (and some films). They owe something to Watchmen (and Frank Miller’s Batman) and, in a sense, are part of its legacy — but for all the wrong reasons.

Moore intended his œuvre to stimulate a reflection on the need so many of us have to follow those with power. Specifically, what’s the point of worshipping superheroes? Can we trust these people to find a way to avert global catastrophe? Or, to be more direct (but still not revealing much): Is it morally acceptable to kill millions in order to save billions?

Unfortunately, many works that came after Watchmen focused only on the most superficial aspects. As Moore lamented,

“There did seem to be a rash of quite heavy, frankly depressing and overtly pretentious super-hero comics that came out in the wake of Watchmen, and I felt to some degree responsible for bringing in a fairly morbid Dark Age. Perhaps I over-burdened the super-hero, made it carry a lot more meaning than the form was ever designed for.”

He was particularly incensed by the way Roschach has become a sort of “anti-hero”, when the story portrays him as someone with extreme views, and leaning towards fascism. It’s true that Roschach sometimes is right, and he is a fascinating character. Moore’s point, however, is that he shouldn’t be praised.

The literary and the visual

Contrary to many who came after them, Moore and Gibbons go way beyond the surface. Nothing is simple in Watchmen. It’s intricate and stimulating like a great novel — in fact, in 2005 Time chose it as one of the 100 best novels written in English since the magazine started in 1923. According to critics Lev Grossman and Richard Lacayo, the story is

“told with ruthless psychological realism, in fugal, overlapping plotlines and gorgeous, cinematic panels rich with repeating motifs.”

Watchmen was the only graphic novel to make it. And it was the intimate embrace between the literary and the visual, which can’t be disentangled from each other, that gave it its unique character. This explains its enormous cultural resonance. Read it, if you will.

The links below were not included in the main text because they are full of spoilers. You have been warned.

Alan Moore’s interviews with GQ …

… and The Guardian

How Watchmen changed comics forever

Watchmen’s impact in the 80s

Why the story is still relevant …

… and influent

“Deconstructing” comics

Amazing the extent of what you are sharing, Luca.