If you drink, don't nuke

Same if you don't drink.

Picture, if you will, a President of the United States deciding to blow North Korea to smithereens in a fit of rage after too much booze. If the first name that comes to your mind is Donald Trump, you couldn’t be more wrong (he is a teetotaller, by the way).

We’re talking about this man:

Cheap tricks

Richard Milhous Nixon, also known as Tricky Dick since the late 40s (due to the dirty tricks employed in his campaign for the US Senate), was a tortured personality. A paranoid, begrudging man, he had a long political career, from House Representative in 1947, to Senator, to Vice-President (under Eisenhower), and finally to President (elected in 1968 and re-elected in 1972, resigning two years later due to the Watergate scandal).

Nixon was capable of the worst: dishonest campaigns, McCarthyism, Watergate, destruction of Cambodia and Laos (in the context of the ongoing Vietnam War). But he could be surprising, making a historic rapprochement with China, as well as starting the détente with the Soviet Union with two milestone arms reduction treaties.

Pills 'n' thrills and bellyaches

He had always been a workaholic and, while far from being alcoholic, could get drunk or at least dizzy with very few drinks. And as Anthony Summers documents in his book The Arrogance Of Power (from which two excerpts were published), this problem was greatly compounded by the regular use of sleeping pills, already during his Senate campaign.

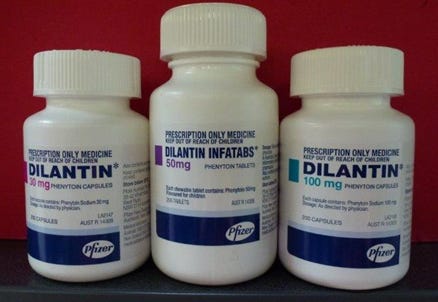

As if that wasn’t bad enough, while campaigning for President in 1968 Nixon started taking an anti-epileptic medicine recommended by a millionaire friend (with no medical expertise) to treat depression. The adverse effects of the drug combined with alcohol and pills made clear thinking very difficult, to say the least. Not a good prospect for the world.

Under his thumb

Nixon went almost over the edge more than once. As his National Security Adviser (and, later, Secretary of State), the war criminal Henry Kissinger, used to say,

"If the president had his way, there would be a nuclear war each week!"

This was an open secret, and not only in the President’s cabinet. In the run-up to the Watergate investigations, Senator Sam Ervin, who would become chair of the Senate Committee, put the matter bluntly in a conversation with a colleague:

“Everyone knew what the prime issue was. A certain thumb moving awkwardly towards a certain red button, a certain question of sanity... Query: if the man who holds the thumb over the button is mad…”

A nightmare on Pennsylvania Avenue

Ervin didn’t know, but this nightmarish scenario almost came true on April 15, 1969. Two North Korean fighter jets shot down an American spy plane over the Sea of Japan, killing all 31 crewmen. According to George Carver, the Administration’s Top CIA Vietnam specialist,

"Nixon became incensed and ordered a tactical nuclear strike... The Joint Chiefs were alerted and asked to recommend targets, but Kissinger got on the phone to them. They agreed not to do anything until Nixon sobered up in the morning."

A fighter pilot on duty in South Korea later revealed that he was ordered to stay on high alert, ready to carry a tactical 330-kiloton bomb (more than 20 times the yield of the Hiroshima bomb). After waiting for a few hours, he was told to stand down.

Two days after the attack, Nixon gave a press conference. There wouldn’t be a military response. He was praised for his diplomatic skills.

However, according to secret documents declassified in 2010, contingency plans for retaliation were being devised since the day of the attack. Nuclear weapons were considered as future options in the report from June 25 (see excerpt below). With typical lack of self-awareness, the plan was called Freedom Drop.

Massive attack

The consensus was that, to avoid an overwhelming response from North Korea against their Southern neighbours, the best option would be a massive attack to disable the country’s Air Force. It wouldn’t be pretty. This revelation helps us understand why the North Korean government has always been so obsessively committed to build a powerful nuclear deterrent.

In the end, common sense prevailed and it was decided that, given the risks involved, diplomacy would be the best way to deal with North Korea. That it took so long to reach this conclusion is what’s really disturbing.

Middle East crisis

Another highly dangerous — and ridiculous — situation happened during the Yom Kippur War, between Egypt and Syria (with support from other Arab countries), and Israel. After the Arab armies mounted a successful surprise attack on October 6, 1973, the Israelis managed to push them back. It took twenty days, but in this brief period the world went to the brink of catastrophe.

During the Cold War, most (if not all) regional conflicts were proxies for the confrontation between the two superpowers, and this was no exception (just as the current Russia-NATO war in Ukraine). With the United States supporting Israel, and the Soviet Union the Arab coalition, the possibility of a dangerous escalation was very high. Was Nixon up the the task?

Situation normal, all f*cked up

On the fifth day of the war, Kissinger, now Secretary of State, received a call from his aide Brent Scowcroft. Looks like the stuff of satire:

Scowcroft: “The switchboard just got a call from 10 Downing Street to inquire whether the president would be available for a call within 30 minutes from the prime minister. The subject would be the Middle East.”

Kissinger: “Can we tell them no? When I talked to the president he was loaded.”

Nixon was distressed — more than usual — by the ongoing Watergate investigation, the disastrous Vietnam War, and the resignation of his Vice-President, the clownish Spiro Agnew, accused of corruption. In the following few days he still managed to discuss with the cabinet matters related to the war, but things would only get worse.

As the crisis mounted, Kissinger, Alexander Haig (Nixon’s Chief of Staff), James Schlesinger (Secretary of Defence), Admiral Thomas Moorer (Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff), and William Colby (Director of the CIA) gradually started to take the reins, as discreetly as possible.

Sleeping while the beds are burning

Things went to a head on October 24, when, after fruitless attempts at a joint solution to the war, the Soviet government decided to act unilaterally. Movements of troops were detected by American intelligence, and the risk of a nuclear conflict became greater by the minute.

After a two-hour phone call between Kissinger and Soviet Ambassador Anatoly Dobrynin, the Secretary of State called Alexander Haig at 9:00 pm, only to be told that Nixon had "retired for the night".

Going all in

So there you have it. The most dangerous situation since the Cuban Missile Crisis, and the President of the United States was AWOL. Kissinger, Haig, Schlesinger, Moorer and Colby had to call the shots, and they chose a huge gamble: the level of nuclear alert was raised to DEFCON 3 (two short of nuclear war), nuclear-armed bombers and submarines started moving, and missile silos were put on alert. They knew the Soviets would become aware of this escalation — so they bluffed, but were terrified of what might happen if it didn’t work.

It worked.

It was not the first, nor the last time that the two superpowers would face the abyss and take a step back. In this case, it was mostly sheer luck.

World, my finger is on the button

This leads us to a question of the utmost importance — should we entrust one single person with the decision to order the launch of nuclear weapons? The Nuclear Launch Authority resides solely on the President, and the order cannot be rescinded. Of course it’s assumed that, before making such a momentous decision, he (or she) will consult military commanders and members of the cabinet, however quickly. But as scholars David S. Jonas and Bryn McWhorter point out,

“History shows that, at times, prior presidents acted while impaired, be it John Kennedy under of the influence of pain killers or Richard Nixon intoxicated from alcohol. In the case of Trump, many questioned his decision-making processes, viewing him as emotional and acting on impulse, often ignoring his advisers. Because of Joe Biden’s age, some people wonder how long he will be able to bring clarity and stamina to the job.”

It is argued that, in a retaliatory attack, the President’s sole authority must be preserved because there will be very few minutes to make a decision. But why should it be the same for a first strike? The President would have enough time to ask for other opinions.

There’s no easy way out

However, if the President is mentally compromised, a decision to kill millions of people could rest on a whim. This is why politicians are calling for some way of constraining that power, at least when it comes to a first strike. A recently drafted bill would make the approval of Congress obligatory. Others defend the participation of the Supreme Court in the process.

There are legal problems though, deriving from the principle of separation of powers. Declaring war is a prerogative of Congress; but it’s the President who chooses the way to conduct war. Involving the Supreme Court would pose a similar problem. The war in Ukraine makes this a pressing issue. But it’s unlikely that things will change in the near future.

Asking the right question

No formal declaration of war has been issued by the US Congress since the end of World War 2. This, of course, didn’t prevent governments to wage war (called by whatever name you wish). So we remain with the original question: can we leave to one single person — whatever their mental state at the time — the fate of mankind?

And here we realise that we have been asking the wrong question. The right question is: should we remain in a situation where it is possible that one single person decides the fate of mankind?

The answer should be obvious.

Thanks, Luca.

I've decided the weapons themselves are a dangerous drug.

I spent the Nixon administration as a politically aware teenager. It was a chilling time to be alive, and we didn't even know he was higher than we were!