Four H-Bombs on a Spanish beach

The Palomares incident was one of the most serious nuclear mishaps in history.

(Note: This article includes highlights of the four episodes of “Palomares”, an award-winning Spanish documentary).

Picture, if you will, walking on a Mediterranean beach in Spain, on a beautiful Winter morning. Then you hear a loud sound, look up to the sky and see a huge explosion. More than 100 tons of debris start falling, including four bombs. Nuclear bombs.

Luckily, they are not armed.

This actually happened, on the morning of January 17, 1966. After a freaky accident involving a B-52 bomber and a tanker during a refuelling operation, four nuclear bombs fell in the vicinity of Palomares, a small fishing village in Southern Spain. Three bombs fell to the ground, and miraculously didn’t hit people or houses. The other one plummeted into the ocean.

As a standard safety measure, the bombs were unarmed (many steps would have to be taken by the crew to release a bomb ready to detonate). Just one armed weapon would be enough to cause a catastrophe.

Each bomb had a yield of 1.1 megaton (the explosive energy of 1.1 million tons of TNT), or about 73 times the bomb dropped on Hiroshima. It wouldn’t be pretty.

This kind of accident is known as a Broken Arrow. According to the official definition,

“A Broken Arrow is defined as an unexpected event involving nuclear weapons that result in the accidental launching, firing, detonating, theft, or loss of the weapon.”

We’ve seen one before:

Welcome to the Displeasure Dome

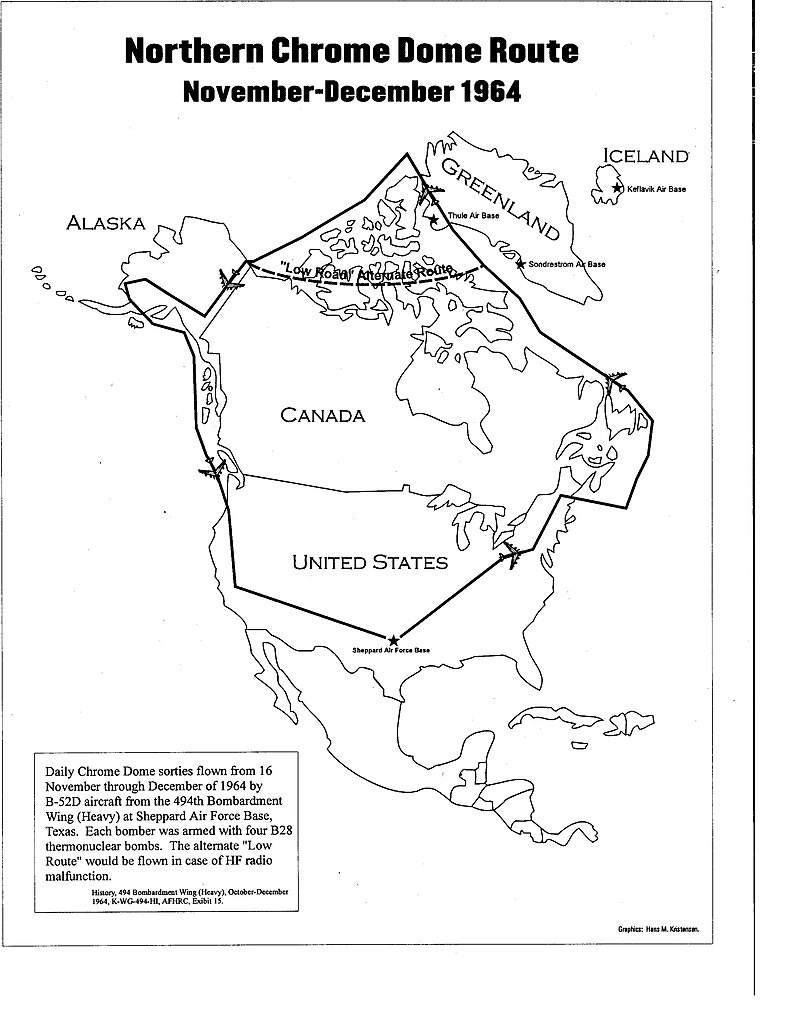

The accident happened during a (very) long-range flight as part of Operation Chrome Dome, established in the early 60s. The successful launch in 1957 of Sputnik, the first man-made satellite, by the Soviet Union, took the United States (and the world) by surprise. Panic ensued: those pesky Ruskies had the technological means to send intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBM) to destroy American bombers still on the ground — or worse, target the United States itself.

Fly me to the USSR

SAC (Strategic Air Command), in charge of the bombers, decided to always have some of them on alert, flying over North America and Europe. This way, they would be able to attack Soviet targets whenever missiles were launched against the US.

Remember Dr Strangelove? That was the idea — and it could obviously go wrong.

As it did. There was no shortage of Broken Arrows (about which I will write in the future), but thankfully none of them led to Armageddon. It was by sheer luck it didn’t happen.

Tragedy in the air

Seven servicemen weren’t that lucky — all the four in the tanker, and three in the bomber. Four crew members who were also in the bomber survived: three of them ejected and parachuted, and the other one, who got stuck in his seat, somehow managed to open his parachute. He was left with severe burns, but alive.

Bombers in nonstop missions have to be refuelled while airborne. This is done by the tankers. One common method is transferring the fuel from the tanker to the bomber through a pipe called a boom (I’m not kidding), with a nozzle at the end.

The B-52 carrying the four bombs would have to be refuelled when flying over Spain, on its return trip from the Eastern Mediterranean to the US. But a tragic failure of communication had the boom’s nozzle striking the top of the bomber, causing an explosion that incinerated the four men in the tanker. The bomber was ripped apart, releasing the four bombs.

One bomb fell to the ground with its safety parachute open, just as the one that went underwater. But the other two crashed — their parachutes failed to activate — and exploded.

It was only the conventional explosives that detonated. If a bomb were armed, this would trigger a nuclear explosion.

All’s well that ends well, right?

Right?

Don’t worry, be dead

Not so fast. The explosions released plutonium, spread in aerosol form through an area of 2.6 square km. The invisible cloud reached homes and the tomato farms in the area.

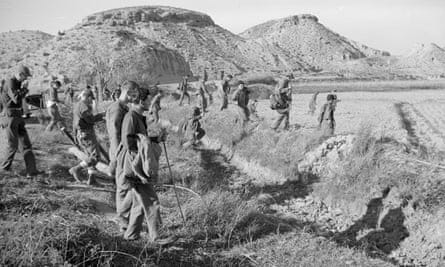

Plutonium in this form is harmful if inhaled. As soon as news of the accident reached the American air bases in Spain (the country was not part of NATO, but had a military agreement with the US), 1,600 low-ranking servicemen were hurriedly dispatched to start cleaning up the terrain. They were told there was nothing to worry about, and started working with no protection whatsoever.

Vamos a la playa

The number of American military in this small village inevitably caught the attention of the public. News of the accident, if not tightly controlled by Franco’s dictatorship, would cause understandable alarm. And this might spell disaster for the Spanish tourism industry, which was booming (sorry) at the time — especially because the fourth bomb was still somewhere under the sea.

To dispel fears, a rather pathetic, but efficient, marketing event was organised two months after the incident. Manuel Fraga Iribarne, Minister of Information and Tourism, and Angier Biddle Duke, the American Ambassador, went to the beach, swimming to show that the waters were safe.

While the show happened at the sea, the clean-up operation on land kept going. The idea was to remove the contaminated soil and ship it to the US for analysis and storage. By mid-March, more than 6,000 sealed barrels were ready for shipping.

This, however, ended up being much less than needed. Episode 2 of the documentary Palomares shows how the American scientist Wright Langham, the world’s foremost authority on plutonium contamination (known as “Mr. Plutonium”) recommended a less stringent approach than the one required by Spanish scientists.

(As an aside, much of Mr. Plutonium’s knowledge came from experiments with human subjects, with the radioactive element being injected without their informed consent.)

The big fish

The priority for the Americans was recovering the underwater bomb. What if the Soviets arrived there first?

More than 20 ships from the US Navy scoured the waters to find it. Sophisticated probabilistic models were used in the search, based on the contribution of a local fisherman, Francisco Simó Orts, who had seen the bomb falling into the sea.

And so it came to pass that the fourth bomb was finally recovered on April 7, almost three months after the accident happened. Orts was now a celebrity, and henceforth became known as “Paco el de la Bomba”. He deserved the fame, since without him, all that technology might have turned out to be worthless.

Salvaging the last bomb was not the end of the story, however. Two nagging questions remain to this day: firstly, the servicemen who were contaminated during the clean-up.

Intolerable cruelty

An article by Jan Beyea and Frank N. von Hippel, published in 2019 in the journal Health Physics, offers a detailed description of the issue, and — what a surprise — Mr. Plutonium was involved.

“The young men worked without protection against inhalation or ingestion of plutonium-contaminated particles. Wright Langham, … who advised on the protection of the men during the operation, later told his colleagues, “the manual says you will dress up in coveralls, booties, cover your hair, wear a respirator, wear gloves.” He explained that none of that was done, however, because of concerns about alarming the local population.”

Many of the military who took part in the operation developed various types of cancers, and those who are still alive keep fighting to receive full compensation (health care and disability). They keep losing, though.

As veteran Ronald R. Howell told The New York Times,

“First they denied I was even there, then they denied there was any radiation … I submit a claim, and they deny. I submit appeal, and they deny. Now I’m all out of appeals … Pretty soon, we’ll all be dead and they will have succeeded at covering this whole thing up.”

Promises, promises

The other problem is the ongoing dispute between Spain and the United States over the removal of contaminated soil, and the corresponding payment. In 2007, a study estimated that there were still up to 50,000 square meters to be cleaned, which harmed the local economy, especially agriculture.

As can be seen in Episode 4 of the Palomares documentary, successive Spanish and American governments have signed agreements and made promises, but nothing has happened. And perhaps nothing ever will.

Small fry

And what about Francisco Simó Orts, the fisherman who played a crucial role in finding the bomb?

Barbara Moran, author of The Day We Lost The H-Bomb (a book about the Palomares incident), tells us what happened.

“Simó guessed he had saved the military at least five days of searching, which he valued at about $1 million a day. He … would use it to educate the children of fishermen and aid the local fishing industry.

The claim went to Washington, where the U.S. government rejected it. Simó hired a New York law firm to represent him, and the case was finally settled in Admiralty Court in 1971. He was awarded $10,000.”

Besides receiving an additional $4,565.56 for his work and the use of his boat, Francisco was awarded a diploma and a medal with a picture of President Lyndon Johnson. He could very well have said: “I helped them find an H-Bomb and (almost) all I got was this lousy medal”.

That region feeds Europa if I am not mistaken.

Never heard of that little incident.These are the same people that say my ownership of firearms is a threat to humanity.