The switch that saved America

A low-voltage device prevented a powerful nuclear weapon from destroying and irradiating a good chunk of North Carolina and the United States' East Coast.

Picture, if you will, a huge nuclear explosion in North Carolina, with more than 40,000 dead and 28,000 injured — and a radioactive fallout reaching as far as Philadelphia. You might ask who the hell would bomb North Carolina, and it would be a sensible question. This could only happen by accident. And it came within a hair’s breadth from happening.

Power to kill people

On January 24, 1961, a B-52G Stratofortress took off from Seymour Johnson Air Force Base in Goldsboro, North Carolina. The bomber was armed with two Mark 39 hydrogen bombs. Each weapon, with a yield of 3.8 megatons, was approximately 250 times more powerful than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima.

We don’t have weapons as destructive as these anymore. The most powerful warheads today have a yield of “only” a bit more than 1 megaton — cold comfort, because they’re more than enough to unleash hell anyway. But throughout the Cold War the explosive yields kept reaching ludicrous heights. The inevitable accidents would become more and more dangerous. Like this one.

Free falling

During the second loop flight, back over North Carolina, the B-52’s right wing burst into flames and the plane began to break up in mid-air. The aircraft started spinning out of control, and its two bombs were released. One of the bombs plunged into a meadow off Big Daddy’s Road (not kidding), near the village of Faro, failing to explode (we’ll get back to it later). Three crew members died. The other five managed to eject safely.

The other bomb, however, followed all the procedures for an attack: it parachuted down as designed, and after that it went through several steps during the fall, including the activation of three out of four arming mechanisms.

(Why the parachutes? To give the bomber a chance to escape destruction. Thanks to John Warnock for the tip)

The last safety mechanism, the one that prevented detonation, was a low-voltage switch. It was set to SAFE, instead of GRD (ground explosion), and didn’t budge. A simple short-circuit, something likely in the extreme conditions experienced by the aircraft, could change its setting.

Nothing happened though. The bomb’s parachute got stuck in a tree and the weapon stayed there until it was removed.

Carolina out of mind

The humble T-249 averted an explosion that would spell doom for vast swathes of the Eastern USA. It would cause more than 48,000 deaths and 28,000 injuries, according to a simulation in the NukeMap website.

The radioactive fallout would reach Philadelphia, as well as Virginia’s East Coast, half of Maryland, the whole Delaware, and half of New Jersey. Washington DC might also be affected, depending on the wind. How many would suffer the effects in the long term is hard to know.

According to historian Alex Wellerstein (creator of NukeMap), this is what the blast would look like:

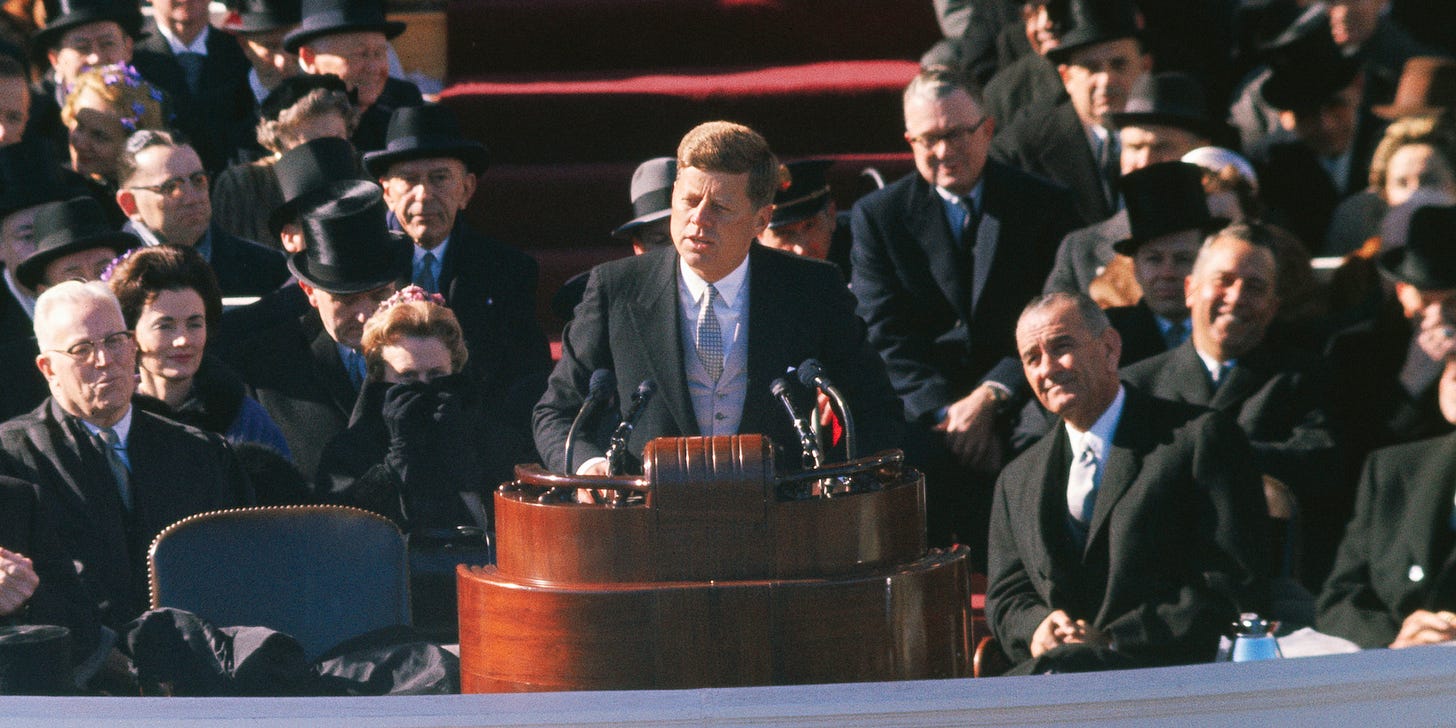

Just imagine this happening four days after John F. Kennedy’s inauguration. Would the accident trigger World War 3 by mistake? Would the new American government publicly acknowledge the fiasco, humiliating the country and putting the President in a bind?

Thankfully nobody had to answer these questions — if there were someone left to answer them.

The incident was classified as a Broken Arrow, the term used by the US military for accidents involving nuclear weapons that do not result in a nuclear detonation. At the time the government maintained that there was never any risk of detonation — because, of course.

A real journalist steps up

It was thanks to the work of an investigative journalist (the kind of which you will never find anymore in the mainstream media) that the truth came out. While researching for his book Command and Control, Eric Schlosser requested classified documents through the FOIA (Freedom of Information Act). He found a treasure trove.

One of the documents was a report on a meeting. Defence Secretary Robert McNamara was very blunt in his assessment of the risk:

“By the slightest margin of chance, literally the failure of two wires to cross, a nuclear explosion was averted.”

Another document was a secret report written in 1969 by Parker F. Jones, senior engineer at Sandia Labs (responsible for weapons safety). As McNamara before him, Jones didn’t mince his words:

“If a short to an ‘arm’ line occurred in a mid-air breakup, a postulate that seems credible, the … bomb could have given a nuclear burst.”

Schlosser also obtained an internal video produced by Sandia for its engineers, part of which recreates the incident:

After all, there was another

The second bomb crashed into a swampy area and broke apart without exploding. Parts of it were buried deep into the ground — including the plutonium and uranium core. Engineer Jack ReVelle, who had been called to dispose of the two bombs, knew immediately that this one would be a tough nut to crack.

When his team managed to find the final switch, the news were disturbing.

“Lieutenant, we found the arm/safe switch,” [a sergeant] told Jack.

“Great,” Jack said.

“Not great,’ the sergeant replied. ‘It’s on arm.’”

It was almost the literal opposite of the other bomb.

ReVelle, using only gloves, was able to find the core and take it to safety. It was the size of a volleyball and he held it against his chest for about 15 minutes. Later in life he would pay dearly for his work disposing of radioactive materials.

Diagnosed with Myeloid Dysplastic Syndrome (MDS), a rare type of blood cancer, he died in January 2020. One month later, after four years of legal battles, the Veterans Association finally agreed to pay benefits. All is bad that ends bad.

To add insult to injury, his widow, Brenda, still had to fight the VA to start receiving their due payments, which started only six months after ReVelle’s death.

Let it go? Not possible

If you think the story ended in 1961, get ready to be disappointed. Parts of the bomb that fell into the swamp are still there. According to the Pentagon,

“A portion of one weapon, containing uranium, could not be recovered despite excavation in the waterlogged farmland to a depth of 50 feet [about 15 meters].”

Those parts are much deeper than that (maybe more than 50 meters), and “quicksand-like” conditions are not conducive to excavations. The Air Force purchased an area with 120m of diameter around the place of the accident, and radiation tests are performed periodically on groundwater.

Be that as it may, the accident won’t be forgotten. A sign remembering the “mishap” is there to make sure the memory remains.

You can buy me a coffee. Or a beer!

Thanks again, Luca.

A detail that might have added something, I think, was that the parachutes were used to give the bomber a chance to escape destruction, and the arming process was designed to take place in sequence as the bomb fell after the parachutes deployed.