Akira, Part 2: the anime, the manga, the bomb

Katsuhiro Otomo's hugely influential masterpiece made manga and anime popular worldwide. It's a cyberpunk dystopia, in the shadow of the ultimate weapon.

Consider this:

Looks a lot like a nuclear blast, right?

This is one of the most impressive scenes in Akira, the anime loosely adapted from the manga of the same name (and created by the same author). The poignant music adds to the drama — and no, it’s not a nuclear blast, but it’s clearly inspired by its grim imagery and destructive power.

It’s not surprising, then, that the animated film was a (metaphorical) blast when it was released in 1988. Akira, the movie, was a masterpiece of animation, visual effects, sound effects, and soundtrack. It showed that Japanese animation could be more than a match for its Western counterpart in artistry and technical achievement.

As we saw in Part 1, the anime was produced and released before the graphic novel was even finished. It was mainly for that reason that the film played a pivotal role in introducing anime to a global audience, and paving the way for the popularity of Japanese animation in many countries.

Akira is not only visually stunning; its complex and mature story-line was not usual in animated films. Just like the manga that inspired it, the anime explores themes such as government corruption, psychic abilities, post-apocalyptic settings, and the potential dangers of unchecked technological and scientific progress.

The depths of the manga

It’s undeniable that, complexity-wise, the graphic novel is light-years ahead — and it was so brilliantly made that it induced an almost visceral emotional engagement. Also undeniable is the fact that faithfully adapting a rich story told in more than 2,000 pages into a film of about two hours is, for all practical purposes, impossible.

The manga delves into the backgrounds and motivations of its characters in greater detail, while offering a richer portrayal of Neo-Tokyo and the world in which the story unfolds. Because of its extended format and the freedom it offers for in-depth storytelling, character development, and world-building, the Akira manga is often considered the definitive version of the narrative.

The dynamics of the anime

The film adaptation, then, falls short of the manga’s depth and expansiveness. But movement, sound, and music, especially on a big screen, involved the audiences in a way that was unheard-of in that kind of film.

Akira, the anime, offered a generous plate of food for thought to a broad audience, and showcased the potential of anime to tell deep and engaging stories in the medium of film. And its worldwide success ended up leading to much greater interest in the manga — especially after it was released in English. Many fans who watched the anime sought out the manga to experience the full story and explore the differences and nuances between the two versions.

What difference does it make? A lot

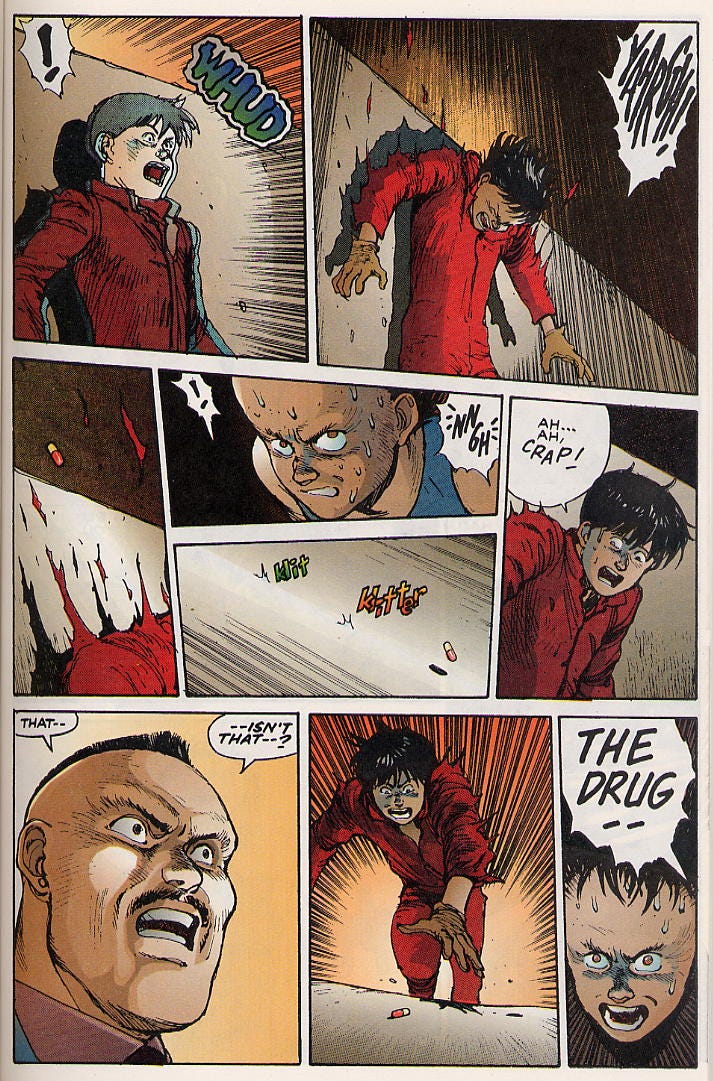

The basic contours of the plot are the same, involving biker gangs, the government’s secret experiments with psychic children, a resistance movement against authoritarianism, and a religious cult — all in Neo-Tokyo, 31 years after the old Tokyo was wiped off the map after a huge explosion, that led to World War 3. A cataclysm that risks happening again: its source may be awaken by a biker whose own psychic powers become manifest.

But there are so many differences that it’s fair to say that we have two different versions of the same basic story, each one well suited to its respective medium. The fact that the manga wasn’t yet finished when the film was produced and released had, as an (almost) inevitable consequence, that these two works would have different endings — the graphic novel would be completed only two years later.

To fit the story within the confines of a feature-length film, the anime had to condense and omit some important plot points, character development, and subplots that were present in the manga. Characters, events, and themes were streamlined or left out entirely — some of them unforgivably so (careful: this link, and the clip below, are chockfull of spoilers).

Nonetheless, it worked. As critic Andrew Osmond said in Empire magazine,

“The film compresses hundreds of manga pages, originally published over several years, into two dazzling but very confused hours of animation. Subplots and support characters are truncated or plain forgotten: plot points are vague, even contradictory … And yet, this messy plot is a big part of Akira’s fascination. More than any sci-fi film since Blade Runner, it hurls the viewer into the middle of a world that bleeds from the screen in multiple hinted backstories.”

Complete control

As a matter of fact, the existence of two distinct versions of Akira (the anime and the manga) has contributed to the enduring legacy of the franchise. Fans often debate which version they prefer and how the differences impact their understanding of the story and its themes.

This happy outcome was only possible because author Katsuhiro Otomo was in full control of the animated version. It was a highly ambitious endeavour: after months of negotiation, the Akira Committee, formed by eight companies and with an enormous (for the time) budget of 10 million dollars, started working. And, think what you will of the differences between the manga and the anime, the film was an aesthetic and technical revolution.

Soft cels

The film used hand-drawn animation combined with innovative techniques, resulting in incredibly detailed and fluid animation sequences. Akira set new standards for what was possible in animated film-making.

Most of the character animation, especially close-ups and intricate details, were hand-drawn. Traditional animation, or cel animation, involves creating individual frames on transparent acetate sheets known as cels (because originally celluloid was used). Classic Disney films were made using the technique.

This labour-intensive process required a large team of skilled animators. Over 160,000 cels were drawn by more than 50 artists.

The use of cels allowed for smooth and consistent character movement, a hallmark of the film. This gave life to the characters and made the action sequences more dynamic.

But this in itself wouldn’t be more than making animation the traditional way. There was much more involved, as Federico Furzan notes in an article for the online magazine MovieWeb:

“Otomo used traditional storyboarding for the whole film. He edited cuts before the artists started drawing. And he made sure to include pre-scored dialogue. No longer would the sound not match the characters' mouths, as they would be animated based on their voice acting and their body movements. Also, the film would include special effects, early CGI animation, and all kinds of resources and elements that were used in the cyberpunk and science fiction genres.”

A visual (master)piece

The integration of cels and CGI (computer-generated imagery) was achieved through a compositing process: combining the hand-drawn character animations on cels with the computer-generated backgrounds and special effects — like explosions, laser beams, energy waves, and whatnot.

The compositing process allowed for the seamless integration of traditional and computer-generated elements, creating a visually stunning and cohesive final product.

As Otomo himself said just after the film was completed, his idea was to create a “total visual piece”:

“There ended up being a lot of cuts, but I knew there would be … I thought of it more as a visual work than as an animation. It was less about making the characters move than about the edits and things you have in a live-action film. I wanted to do something more technical with the visuals. Of course, we do animate the characters … [but] I wanted to create this movie as more of a total visual piece.”

The use of pre-recorded voices, creating the animations later to match them (pre-scoring), allowed for a precise synching of voice and mouth, as well as more realistic (so to speak) face and body motion.

Another innovation was the use of the Synclavier, one of the earliest synthesizers, controlled by a computer workstation. It made possible the manipulation of sounds through a keyboard, generating effects that greatly enriched the film’s environment.

The soundtrack excels. Otomo was looking for “something ethnic, with more rhythm”. He chose the musical collective Geinoh Yamashirogumi, who play folk music (from the most diverse origins), combining choirs, traditional instruments, and high technology. In the Akira Symphonic Suite, this results in a hauntingly evocative music, as you can hear below.

Slide show

Akira is deeply ingrained in popular culture. It played a significant role in popularising the cyberpunk genre, with its dystopian futures, advanced technology, and social decay — and inspired countless other works, from films and television shows to video games and music.

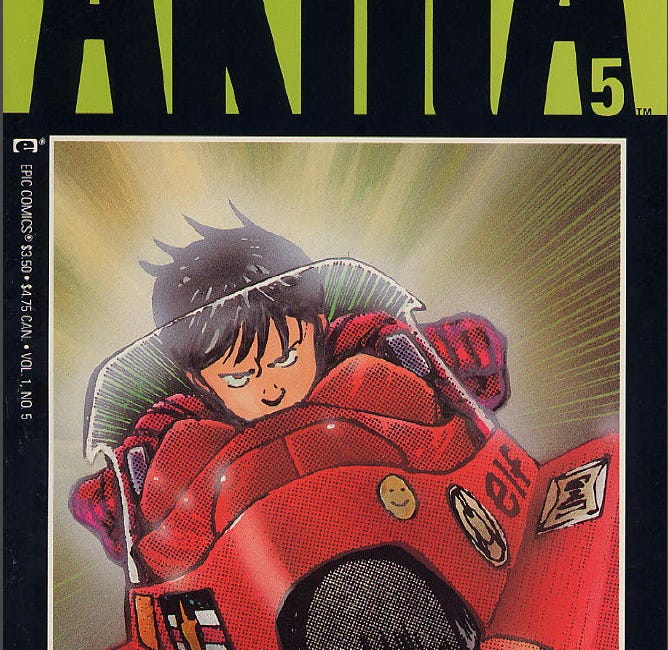

The imagery of the film, including the iconic red motorcycle (inspired by the film Tron) remains recognisable to this day. The “Akira slide” (below) would become an inescapable reference in many films and shows. The colour palette was so rich that there is even an Akira Red.

Cyberpunk was not the only inspiration for Otomo’s work, though. In his book Schoolgirl Milky Crisis, historian Jonathan Clements explains that Otomo’s life was also an important source of ideas (p. 35):

“Most critics see little further than Blade Runner when looking for influences on Akira, but real life provided plenty of inspiration. When Otomo was in his teens, Japan hosted the Olympics, there were riots in the streets over a Security Treaty with the United States, and students-turned-terrorists died in a gunfight with police in the resort town of Karuizawa.”

But the truth is, this specifically Japanese situation was eventually transcended by Akira and other works that followed. The result was a profound and lasting influence on cinema, music, and various other art forms. Just a few examples:

The Matrix (1999): One the greatest films of all time (with three of the worst sequels of all time), directed by the Wachowskis, drew inspiration from Akira in its visual style, a dystopian future, and the fusion of Eastern and Western philosophies. The "bullet time" effects were reminiscent of some of the action sequences in Akira.

Chronicle (2012): This found footage-style superhero film, directed by Josh Trank, was influenced by Akira in its depiction of young people gaining powerful telekinetic abilities and the consequences that come with them.

Looper (2012): Rian Johnson's time-travel sci-fi film features telekinesis, which is reminiscent of the psychic powers showcased in Akira. The psychic boy, Cid, plays a fundamental role in the film’s ending.

Stranger Things" (2016–present): Well, this one is easy. Akira is one of the show’s many 1980s pop culture references. The character Eleven was clearly inspired by the Espers, the psychic, unnaturally wizened children who are part of a secret project.

Deus Ex (2000): One of the many futuristic, dark, and very smart computer games who owe a lot to Akira. So much so that Deus Ex: Mankind Divided (2016), the fifth instalment in the series, had a tribute poster to the anime.

Ghost in the Shell (1995): Another great cyberpunk anime, this classic became one of the main references for the genre. The film is set in a future where people’s brains are jacked in computer networks, while hackers try to gain control of their minds. Lots of influences here, from William Gibson’s novel Neuromancer to Akira.

Stronger (2007): The video for this brilliant song by Kanye West (with special guests Daft Punk) is full of scenes recreated from Akira, as well a visual style that matches the anime. Even the motorbike chases have the same effects as shown in the film.

Check this out:

Akira: An analysis of the A-Bomb and Japanese animation

Interview with Katsuhiro Omoto about sound effects, soundtrack and CGI:

Manga vs Anime: the never-ending debate

Kirby Ferguson and his team made a video about the influence of anime, East Asian cinema, and sci-fi on The Matrix, in the Everything Is a Remix series: