Duck and Cover till it's over

A short film for schoolchildren introduced a generation to the imminent threat of a nuclear attack. Was it propaganda or useful advice? Or both?

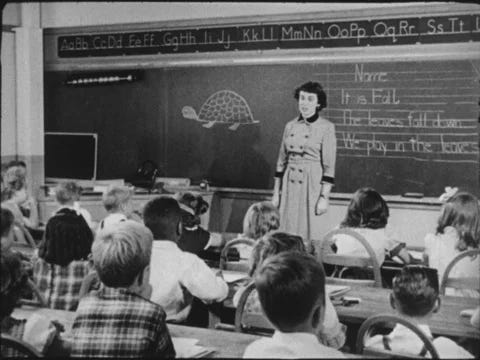

Picture, if you will, schoolchildren hiding under their classroom desks, waiting for the worst to happen. No, it’s not an active shooter drill. I’m talking about Duck and Cover, an educational film screened in American schools from the early 50s onwards. Its purpose was to teach kids how to act in case an atom bomb exploded.

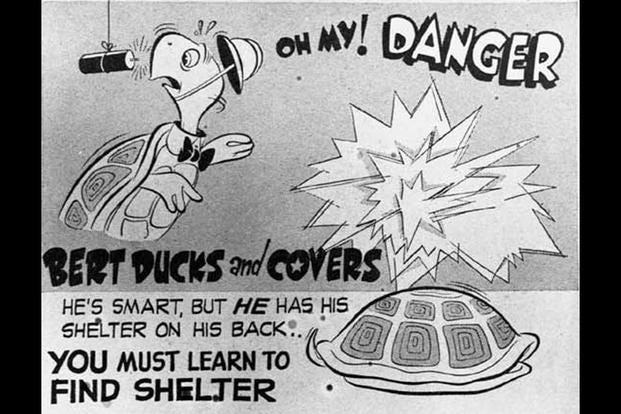

This civil defence training film has, as it main character, the cartoon Bert The Turtle. He carries a shelter on his back, after all. Whenever there is danger, Bert hides into his shell and stays put until it’s (allegedly) safe to get back to normal.

But why submit youngsters to this?

The Russians are coming

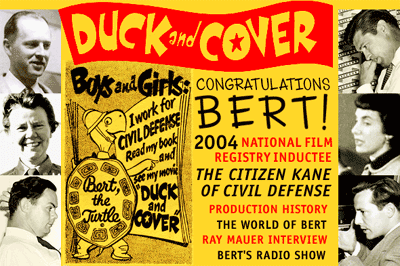

It all began a couple of years earlier. The first successful test of an A-bomb by the Soviet Union, in 1949, ended the American nuclear monopoly. Alarmed, the Truman Administration decided to establish a national Civil Defence programme of training for all citizens — basically, “duck and cover” drills. It started in 1950, and a campaign was devised for kids. Production started in 1951 and the film was released in January the following year.

Dubbed, hopefully in jest, “The Citizen Kane of Civil Defense” (just imagine the quality of the other films), Duck and Cover is a rather naïve, well-intentioned but irremediably (if unwittingly) campy work. Almost all actors are amateurs, with teachers and students playing themselves.

But they do it in earnest. It’s a civil service, after all. The instructions are the easiest possible: duck and cover. That’s it. But when to do so? There are two scenarios.

Warning, live without warning

If there is a warning, you must head home or find a secure place as soon as you hear the ominous siren sound. Failing that, ask someone for help.

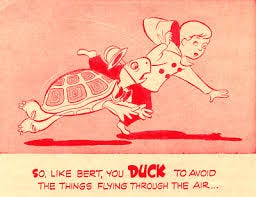

If the attack is launched without warning, the flash is the key sign. Whenever there’s a sudden, blinding flash of light, duck and put your hands over the head. Most examples take place in classrooms and other closed spaces. But there could also be situations in which that happens in the open. You have to do the same and, if possible, try to find a place, small as it may be, to hide. At least you will be spared some of the debris flying at high speed with the blast.

The flash of light is the first thing we can perceive when a nuclear weapon explodes, much earlier than the sound (the speed of light is much faster than the speed of sound). So it makes sense to use it as the signal to duck. But how to convey this message to kids?

A hard sell

Fires and cars are mentioned as examples of dangerous stuff, following the directive “Warn, but don’t frighten” to avoid traumatizing the kids. But when it comes to nuclear weapons, this is nigh impossible to achieve:

“The atomic bomb flash could burn you, worse than a terrible sunburn. Especially where you are not covered.”

The narrator’s monotone voice only adds to the feeling of dread. And it isn’t surprising that many children subjected to drills like this trough the years would later become anti-war activists. As sociologist Todd Gitlin recalled,

“We grew up taking cover in school drills — the first American generation compelled from infancy to fear not only war but the end of days.”

The new normal

But it was the opposite effect that seemed to prevail: people becoming complacent because of the constant drilling.

It is for this reason that scholars have accused the campaign of being propaganda to normalize an unacceptable situation. As historian Dee Garrison pointed out,

“The civil defense propaganda of the early 1950s was a deliberate and conscious effort by government to bring public thought into line with national security policy through shaping public attitudes toward nuclear war. This plan relied on a system of emotion management that would suppress an uncontrollable terror of nuclear bombs and encourage in its stead a more pliable nuclear fear.” (page 47)

Duck and Cover ended up being ridiculed for many years, even in a South Park episode.

The film has been widely viewed as a relic of a time when the US was by far the richer and most developed country in the world, while at the same time exploiting the fear of atomic weapons and, of course, the Red Scare.

According to the Conelrad blog, dedicated to the bomb’s “pop culture fallout”,

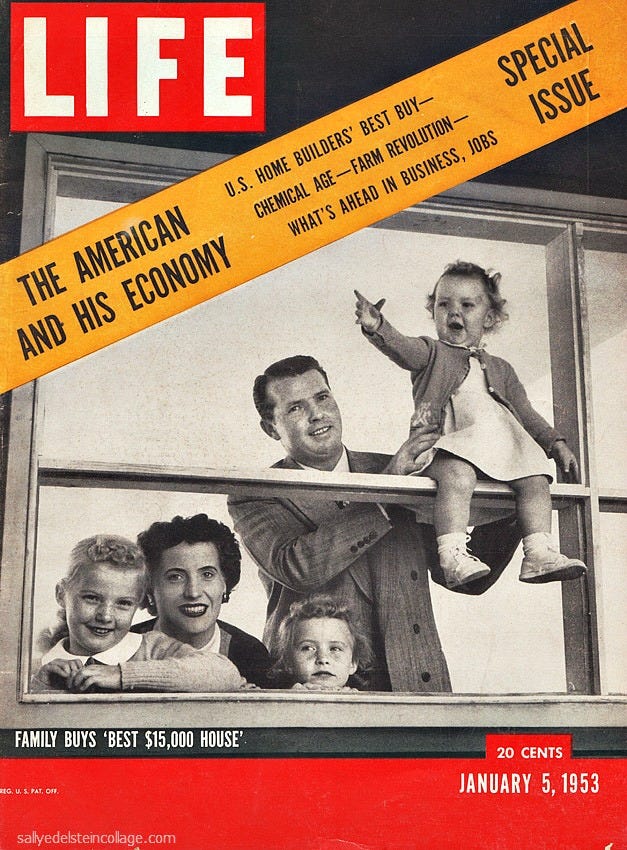

“In many ways Duck and Cover is the perfect synthesis of the competing themes of the 1950's: Fear and prosperity.”

It had its uses, for a time

Today, however, there is some acknowledgment that Duck and Cover served a useful purpose — at least in its very first years, before thermonuclear weapons (hydrogen bombs) became widespread. Fission bombs, like the ones dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, would be considered modest in their destructive power against the new kid on the block (thermonuclear weapons use fission to trigger fusion). And there were no missiles yet.

Historian Alex Wellerstein (creator of the NukeMap website) tries to put things in perspective:

“Bert the Turtle is a bit condescending, but he was aimed at children, and for 1951 his message isn’t too far off. In 1951 the Soviets still lacked ICBMs and had bombs no more than double the yield of the Nagasaki weapon. Hiding under your desk probably wouldn’t help you much if the bomb went off right over your head, but could be significant for all of the people who were within a mile or so of the blast.”

In fact, the degree of protection would depend on many factors besides distance and the bomb’s yield. Thermal radiation comes with the flash light and can cause horrible burns (in extreme cases your skin can peel off) as well as blindness. Never look straight at the light source (which is basic common sense, after all).

The best use for a newspaper

The good news (so to speak) is that even using a newspaper for protection, as it happens in the film, can mitigate the effects of thermal radiation. Ducking and covering also helps reducing the damaging effects of the blast wave.

These findings are based on how people in Hiroshima and Nagasaki were affected by the bombs. But as we know, the nuclear arsenal became almost unimaginably destructive in the many years that followed. Looks like Duck and Cover became hopelessly dated. But it doesn’t hurt to try. If a dazzling light suddenly appears out of nowhere, and you’re still alive, duck and cover. Then pray.

You can buy me a coffee. Or a beer!

I hit kindergarten in '59, but Duck and Cover was still in use in my early grade school days. So were the drills. By the Cuban missile crisis, I was scared to death. Fortunately, my parents were reasonably cool and reassuring.