1983: The year of living dangerously

Belligerent rhetoric, paranoia, tragedy, and near misses turned 1983 into the closest we have been to a nuclear war since the Cuban Missile Crisis

Picture, if you will, hundreds of nuclear missiles being deployed in Western Europe to face hundreds of nuclear missiles in Eastern Europe. What would you do? Babble inanely about “values” or actually try to do something about it? Forty years ago, millions chose the latter. Today, millions choose the former. This is why it’s important to rescue those years from the memory hole.

And in the turbulent 80s, no year was more frightening than 1983. Actually it became even more frightening later, as we had access to previously classified information.

Reckless rhetoric

On March 8, 1983, American President Ronald Reagan, already known for his belligerent public posture towards the Soviet Union, called the USSR an “evil empire”, in a speech to the National Association of Evangelicals. Besides the reckless rhetoric, the speech reinforced the view that many people had of Reagan: an ignorant would-be cowboy bent on conflict.

Just two weeks later, Reagan announced the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI), which would become known as “Star Wars”. The idea was to have satellites equipped with lasers to destroy any ICBM (Intercontinental Ballistic Missile) launched by the USSR against the United States (ICBMs leave the atmosphere during their trajectories).

“Star Wars” would jeopardize the doctrine of Mutually Assured Destruction, or MAD, the whole point of which was the guarantee that whoever struck first would face a devastating response — so nobody would take the risk. By potentially neutralizing their opponent’s missiles, the United States could wipe them out without fear of retaliation.

State of paranoia

Reagan picked up the idea from the physicist Edward Teller, “father” of the hydrogen bomb and unrepentant warmonger. Despite the president’s public assurances that the project was purely defensive, it’s understandable that the Soviets would have a hard time believing he was sincere.

But the Soviet leadership was not just suspicious; they were paranoid. The new leader, Yuri Andropov, former head of the KGB, was representative of the establishment’s opinion, convinced of an American ploy to strike first and “decapitate” the USSR before it could respond. Reagan’s “evil empire” remarks (unprecedented in the history of the Cold War) and the “Star Wars” announcement just reinforced their beliefs.

Ship of fools

The SDI was, as it turned out, pure vaporware (to borrow a term from the computer industry). It was also a hoax. The results of a crucial test were falsified, but duly reported as true by the media. And the $30 billion program managed to fool the Soviets into spending larger and larger amounts of money, with damaging consequences to the economy — as well as fooling the American public into supporting an increasingly bloated Defence budget, in the interests of the Military-Industrial Complex.

Reagan believed in it though. And so did the Soviet leadership. Andropov reacted with indignation at what he perceived as a grave threat to the USSR. After all, how could he trust someone who, just two weeks earlier, called his country an “evil empire”?

Life of RYaN

Project RYaN (an acronym for “Nuclear Missile Attack” in Russian) was the biggest peacetime intelligence operation in Soviet history. RYaN was established by the Soviet intelligence agencies (KGB and GRU) in 1981, coordinated with the secret services of the other Warsaw Pact countries — especially East Germany. Their mission was to detect the slightest indication that a nuclear attack on the country was imminent. The operation only started picking up steam in 1983, reflecting the increasing tension.

Spies in Western capitals and other major cities had to monitor whatever could be a sign of an imminent attack. Most directives were sensible, but others were far from it — like checking if religious leaders went into hiding. Actually anything and everything might point to a nuclear attack. The planned deployment of Pershing II and cruise missiles in Western Europe only added to the paranoia. And then a tragedy happened.

Tragedy of errors

In the early hours of August 31, the Korean Airlines Flight 007 (KAL007) took off from Anchorage, Alaska, the stopover in the trip from New York to Seoul. What happened from then on was a literally disastrous application of Murphy’s Law: a sequence of errors that led to the commercial airplane being shot down by a Soviet fighter. All 269 people on board died.

The plane started to drift north about 30 minutes after taking off. It was established later that the most likely explanation was a problem with the autopilot — either it was wrongly set, or didn’t work properly. Anyway, the crew didn’t detect the deviation. When it reached the Sakhalin Island, the plane was more than 300 km away from the planned route.

Soviet air defence was already in high alert because, at the same time, an American spy plane was in a reconnaissance mission nearby. A mixture of misunderstandings, miscommunication, high tension and bad luck ensued, and KAL-007 was shot by a Sukhoi Su-15 fighter, ending its trip at the bottom of the ocean. It was early morning of September 1st. The plane had just crossed the International Date Line.

The Soviet authorities initially tried to deny responsibility, but eventually had to admit it — while maintaining that the shooting was justified. Reagan called it a “massacre”, an “act of barbarism”, and a “crime against humanity”. Tension was in the air, everywhere you looked around.

Under pressure

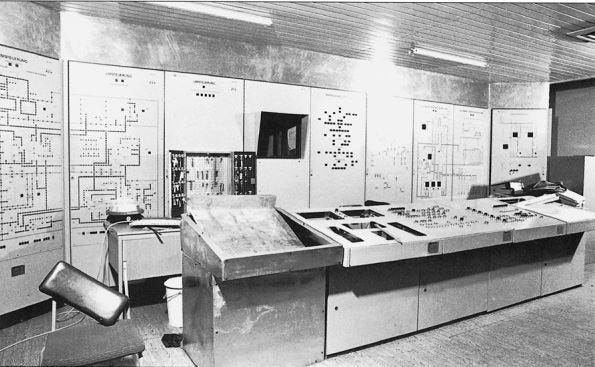

But the most dangerous moment of the year was overlooked — and only became known many years later. At 12:15 AM, September 26, Lieutenant Colonel Stanislav Petrov, on duty at the command centre of a nuclear early-warning system south of Moscow, saw the unthinkable: the order to LAUNCH, in big red letters, on a panel at the top of the room. According to a satellite, an intercontinental ballistic missile was on its way from the United States to the USSR. It would arrive in 35 minutes.

This lonely traveller was dismissed as a glitch, but a few minutes later, more missiles were detected. Now there were five in total. Petrov had very little time to report to his commanders. Common sense and intuition led him to conclude that this was not what it seemed. The Soviets expected any surprise attack from the US to be massive — five missiles didn’t fit the bill. And there wasn’t any confirmation from radar stations. It might be early for them detect anything, but Petrov decided to inform his superiors that it was a false alarm.

Did he save the world that night? He may have. But the story will be told in a future post.

No nukes

There were however very real missiles stirring up rebellion in Western Europe. In the late 70s the Soviet Union deployed 130 SS-20 intermediate range missiles in their own territory as well as in Warsaw Pact countries. In response, NATO decided to deploy the American intermediate range missiles Pershing II in West Germany, and BGM-109G Gryphon in the United Kingdom, Italy, Belgium, and West Germany (again).

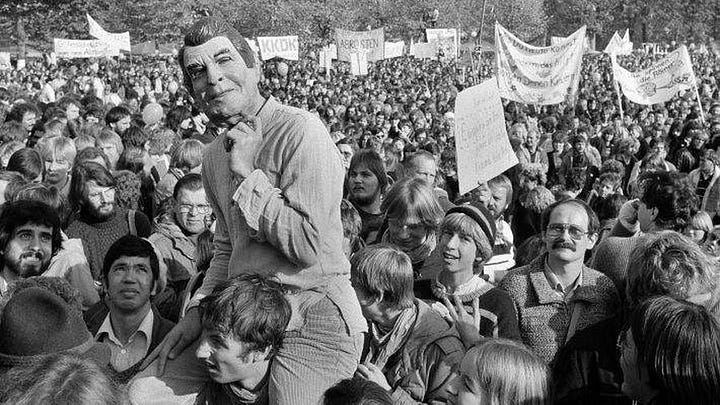

But people would have none of it. A huge anti-war movement spread from Europe to the rest of the world, with millions demonstrating against nuclear escalation by both sides. Starting two years earlier, demonstrators against NATO and the Warsaw Pact took to the streets, and the movement reached its peak on October 23, when more than 1 million people marched in West Germany. Throughout the month, protests gathered more than 3 million people in Europe — the largest pacifist demonstrations until then.

Demonstrations continued the following years, but the missiles were deployed anyway. This doesn’t mean that the anti-war movement was defeated, however. It was part of an overall political debate that led to the signing of the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) Treaty in 1987. Reagan, who was already having second thoughts about nuclear escalation, signed the treaty with the new Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev. More than 2,500 missiles were destroyed until 1991.

Shooting the wrong target

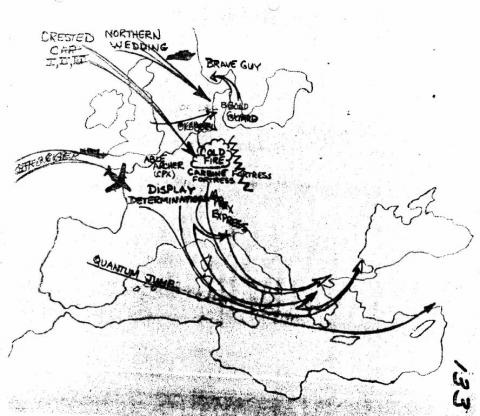

While all this was happening, and as if it wasn’t too much already, on November 7 NATO launched its most ambitious and realistic military exercise to date. The annual Able Archer wargame was very different from its previous iterations. It simulated in detail the Command, Control, and Communications (C3) procedures of the NATO forces, and the deployment of American troops. Dummy warheads were used, and political leaders like Margaret Thatcher (British Prime-Minister) and Helmut Kohl (German Chancellor) participated.

The preparations for Able Archer 83 were anxiously followed by Project RYaN. Many Soviet officials were convinced that the exercise would be a cover for the much dreaded first strike. The realism of the war game only exacerbated the paranoia — especially when the NATO command moved the level of alertness (in the exercise) to DEFCON 1, meaning that nuclear war was imminent or had already started.

Unbeknownst to the NATO command, the Soviets took this seriously. So much so that 70 SS-20 missiles were put on high alert, and airplanes in Poland and East Germany were loaded with nuclear bombs.

Better do nothing

Lieutenant General Leonard Perroots, Assistant Chief of Staff of the US Air Force in Europe, received reports of unusual movements by the Warsaw Pact forces, including 36 surveillance flights. Another report indicated suspicious munition being loaded. Perroots decided not to do anything — avoiding a response that might lead to a disastrous escalation.

The extent to which the Soviet leadership was poised to attack has been disputed, since just a small part of their armed forces was put on high alert. Be that as it may, this was yet another situation that could have spiralled out of control because of minor mistakes.

The crisis was put to rest when the exercise ended, on November 11. The year was almost over. A hell of a year, indeed.

Hey, that's a great summary of 1983. I'd forgotten how much happened. That was the year I got married, so if any of the event you remind us of had gotten out of hand, I sure would have missed out on a LOT. I was ten years old living in Florida at the time of the Cuban Missile Crisis, another near miss which could have ended my life before it had much of a chance to begin.

Commentary: Reagan called the Soviet Union an "evil empire" because it was an evil empire. Sadly, the Russian people have not yet escaped evil governments, as we see today in Ukraine. Anyway, a considerable number of people can get confused about such things, so sometimes it's helpful to just say it like it is, and label things plainly.